Inside Boston University’s sprawling 808 Gallery, “Tago ng Tago (Hidden and Hiding),” a solo exhibition of works by Filipino artist Bhen Alan, is playing tricks. In the center of the front wall, Three Hundred Thirty Three (2022), a 95-by-62-inch multimedia weaving, seems to be moving. It’s not; while the 808 Gallery’s broad wall of windows lets in the bright, slanting light of this early November day, it allows for no breeze that might ruffle the coconut leaves or send the threads that trickle down beyond the bottom edge of the piece skimming across the floor. No, the work hangs still, exuberantly yellow, soft with yarn, stiff with dried reeds, boldly claiming its space as an emblem of queer, Filipino splendor.

Online Only• Nov 30, 2022

Woven Choreographies: Inside the Movement with Bhen Alan

The artist’s vibrant multimedia weavings draw on his love of dance and his wide range of disciplines, influences, and past experiences. Now, he’s returning to his roots.

Profile by Jessica Shearer

Drawing from a wide array of disciplines and influences, Filipino artist Bhen Alan creates weavings that he often activates through movement. As part of his Fulbright scholarship, he is researching the Indigenous weaving practices of the Philippines. Here, in Agutayan, Balabac, Palawan, he (left) learns from Norbena (right), who has been weaving since she was a young girl. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Drawing from a wide array of disciplines and influences, Filipino artist Bhen Alan creates weavings that he often activates through movement. As part of his Fulbright scholarship, he is researching the Indigenous weaving practices of the Philippines. Here, in Agutayan, Balabac, Palawan, he (left) learns from Norbena (right), who has been weaving since she was a young girl. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Bhen Alan, Three Hundred Thirty Three, 2022. Woven rice sack and canvas, fans, coconut leaves, abaca, sinamay, bamboo leaves, feathers, found yarn, found thread, fabrics, palaspas, rattan, and industrial plastic fence on stretcher bar. 95″ x 62″. Courtesy of the artist.

And yet I keep catching it move. Perhaps it’s because bisecting the lime-green zig-zagging stripes in the lower right and the neat rows of rattan standing plumb in the upper left is a snaking coil of material, cinched in the center by a fluorescent feathered fan and arcing out to the upper right with shimmering tulle and floral fabric, a fabulous twist that whirls off like some brilliant flushed bird or—more aptly—a spinning dancer.

Apt because dance was Alan’s first and most foundational form of expression. Through movement, he made use of an innate talent while upholding the rituals of his ancestors. “When I was growing up in the Philippines, I was trained to dance folk dances—cultural dances—to preserve our culture and traditions, and especially our stories,” he said. “There are a lot of stories involved in the movement and in the choreography itself that you can’t articulate verbally.”

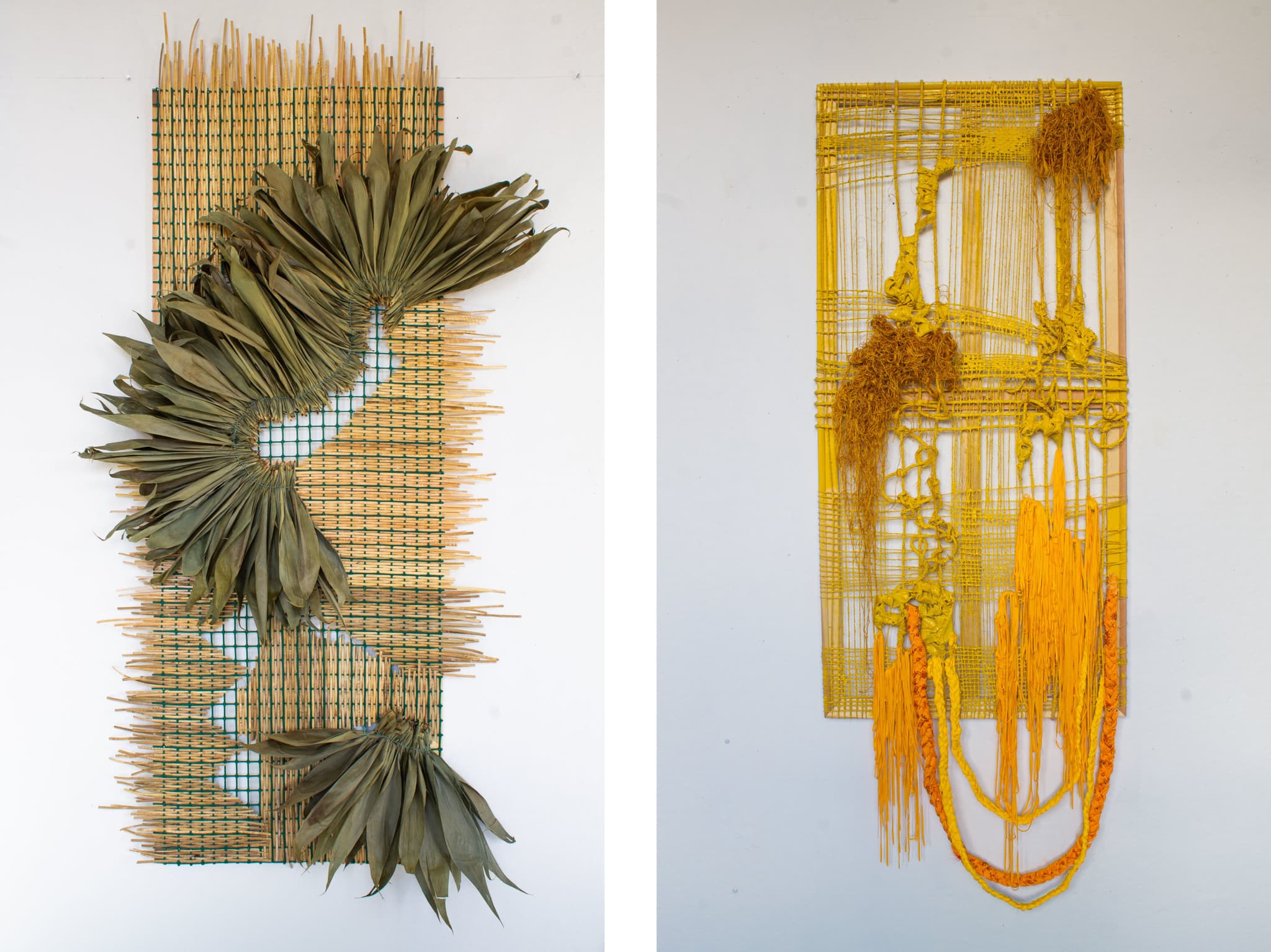

The language of dance is everywhere in Alan’s work, from the wending knotted bamboo leaves of Tinikling (2022) to the painted, pendant fibers of Singkil (2022)—both of which are titled after traditional Filipino folk dances.

Left: Bhen Alan, Tinikling, 2022. Rattan, bamboo leaves, and industrial fence on stretcher bar. 80″ x 40″. Right: Bhen Alan, Singkil, 2022. Twine, fabric, yarn, thread, and paint on stretcher bar. 62″ x 23″. Photos courtesy of the artist.

It is through movement that Alan takes up space. His works, which he often activates through dance and performance, occupy territories that bridge the opposing aspects—masculine and feminine, native and outsider, intuitive and rational—that define his own personal identity and speak to queer and immigrant experiences more broadly.

“When I tried to fit in, I became invisible,” he said. “So I began to manipulate what I show, and I try to hide things. With my work, I want to showcase my movement, my fluidity, my body, my gesture, my approach to life, and overpower those hard, masculine moments.”

Alan’s worldbuilding—his careful melding of disciplines and influences—is what attracted me to him in the first place. Whether vibrant and tangled or quiet and orderly, his painted weavings have resonated with a wide range of audiences, resulting in a banner year. Following his thesis show at the Rhode Island School for Design (RISD), where he earned a master’s in painting (more on that later), Alan organized the Diasporic Threads Filipino heritage festival and challenged traditional imperialist narratives by wrapping The Hiker, a public monument memorializing soldiers who fought to colonize the Philippines, in a massive baníg, a traditional handwoven mat. Later, I’d see that same piece in motion during a performance at Praise Shadows Art Gallery in support of the group show “shape_shifting_support_systems,” where his four works charted a rejection of conformity through increased abstraction, beginning with the tidy indigoes and whites that patterned Nanang (2022) and culminating in the wild escape of Dororong (2022), an explosion of electric pinks.

Four works by Bhen Alan explored a rejection of conformity through increased abstraction at the “shape_shifting_support_systems” exhibition at Praise Shadows Art Gallery. The process moved from right to left: Nanang, Three Hundred Thirty Three, Mermaid’s Tail, Dororong, 2022. Photo by Dan Watkins for Praise Shadows Art Gallery.

Right now, Alan is in the Philippines researching Indigenous weaving techniques as part of his Fulbright Scholarship (2022 really has been a hell of a year), but you can see the aforementioned piece, also titled Diasporic Threads (2021–2022), at 808 Gallery. At 20 by 10 feet, it takes up an entire wall and even some floor space, and like much of his work, it’s created from found materials, in this case tarps, strips of Amazon packaging, and art-student canvas castoffs.

Like his practice, a conversation with Alan is underscored and punctuated by movement. During our Zoom call earlier this month, though his figure was pixelated and rendered in miniature, he thrummed with a taut, propulsive energy that ricocheted between contained, concentrated stillness and wide, looping, gestural sweeps, with hands in constant motion and a smile that rocked his whole body back.

This dichotomy—his ability to spring from meticulous to expansive, from attentive to giggling—finds its source in a personal history marked by connection, displacement, and tenacity.

“My father died when I was two and my mom left me when I was seven to go abroad to support me,” Alan said. “And so I was left to my grandmother and my community.”

Though scarred by loss, Alan describes his childhood as one of happy abundance, where he was raised collectively in Tuguegarao City, Cagayan. “Being the only child in my family, the whole village took care of me like their own kid. Everyone was teaching me everything, from farming and making baskets to planting, harvesting, dancing, chanting, singing—everything that I can think of.”

Installation view of “Tago ng Tago (Hidden and Hiding),” on view at Boston University’s 808 Gallery November 3–December 1, 2022. Front left: Bhen Alan, When My Mother Left Me, 2022. Woven rattan, fabrics, abaca, woven baskets, and industrial fence. 9′ x 8′. Photo by Rosa Jang, courtesy of the gallery.

Alan’s practice is informed by his ability to draw from his vast array of skills and experiences to fashion magnificent amalgamations, but straddling dualities isn’t a painless exercise. Sometimes, the void is laid bare, as is evidenced clearly in the installation hanging on one of the gallery’s far floating walls. When My Mother Left Me (2022) is composed of the materials that make up his single weavings, including rattan, fabrics, abaca, woven baskets, and red industrial fencing, yet this work is a collection of disparate items rather than a unified whole, depicting facets of the artist’s nature that, at seven years old, had not yet coalesced—and the road would get rougher before they did.

At seventeen, Alan was immersed in a competitive dance practice that had taken him across the country and back, and he had enrolled as a first-year student at the University of Saint Louis Tuguegarao. Yet when he reconnected with his mother, he decided to join her in Canada, leaving his community and his artistic outlet behind. To call the move a culture shock would be an understatement.

“We were completely isolated from other Filipinos, and I was so homesick. I didn’t know anybody. I didn’t know English,” he said. “I didn’t even really know my mom at the time; we hadn’t seen each other for ten years. And there’s nowhere to dance. I feel like I can’t move, like I’m not free. I can’t move my body, I can’t move my muscle. I can’t move my mouth; my brain isn’t working.”

And so he began to paint, staging still lives on the toilet in the opulent bathroom in the apartment he shared with his mother.

“My mother’s employers offered us space to live in their basement, and while we didn’t have anything in our little room, we had this beautiful, beautiful bathroom, and there I was putting oranges and grapes on the toilet and painting,” he said. “I thought, maybe I can use this as a form of therapy—a form of communication with myself. Maybe I can cling to this.”

Installation view of “Tago ng Tago (Hidden and Hiding),” on view at Boston University’s 808 Gallery November 3–December 1, 2022. Alan has activated the center weaving, Diasporic Threads (2021–2022), in multiple performances. Photo by Jessica Shearer.

After an early piece was snatched up by one of his mother’s employers, Alan threw himself into his painting practice, soaking up everything he could learn from Bristol Community College in Fall River, then UMass Dartmouth, and finally his master’s program at RISD.

At school, surrounded by like-minded peers, bolstered by academic instruction and familial support, he found the dynamics that attracted him to painting were beginning to lose their luster. Rather than acting as an emancipating vehicle for a muted mind, the practice felt stifling and suffocating—immobilizing.

Just one week into the painting program, there was a moment of epiphany. Rather than hamstring himself by engaging in a single discipline, he could tap into his roots and mine his past for a broader, more expansive arsenal of inspiration.

“I started borrowing from my dancing experiences and my weaving experiences from the Philippines,” he said. “All of it—chanting and singing—I put it all into practice.”

That moment was the genesis of all the work that has preceded his Fulbright scholarship. It also began a balancing act of disclosure and concealment as Alan tried to navigate how to publicly express his heritage, his immigrant experiences, and, increasingly, his queer identity. “My family always knew I was gay, and they were okay with it—but they wanted me to hide it to protect the family name,” he said. “I was raised to present as straight and traditionally masculine, and that shows up in my work—there’s a rigidity, but I try to overpower it with fluidity, with movement, because that’s when I feel that I’m accepted, when I’m moving.”

Right: Bhen Alan, Mermaid’s Tail, 2022. Rattan, fabric, abaca, and industrial plastic fence on stretcher bar. 72″ x 51″. Left: Bhen Alan, Midday Landscape in the Orient, 2022. Rattan and industrial plastic fence on stretcher bar. 84″ x 60″. Photos courtesy of the artist.

The push and pull between legibility and illegibility, exposure and evasion, may be most apparent through performance, but is also eloquently expressed in his weavings, which range from the resplendent blues and glossy golds of Mermaid’s Tail (2022) to the restful geometries of Midday Landscape in the Orient (2022), which is solely composed of rattan woven through stretched industrial plastic fence.

With rosaries, shells, and other hidden talismans nestled into their fibers, their flossed expanses winking with empty gaps, his pieces are defined as much by what is absent as what is incorporated, what they display versus what they shield. They reflect Alan’s own level of comfort with presenting cultural signifiers; the artist is strategic about how—and to what extent—his pieces translate his heritage to a wider audience.

During his Pagbawi (“pag-ba-wi”) | Reclaiming performance at Praise Shadows Art Gallery, Alan modified a traditional Filipino dance and chant, activating his Diasporic Threads (2022) baníg. Photo by Jessica Shearer.

As such, Alan’s works often act as both adornment and armor. When I saw him at Praise Shadows this summer in a performance titled Pagbawi (“pag-ba-wi”) | Reclaiming, the Diasporic Threads baníg that cloaked The Hiker statue earlier this year assumed those dual roles while he executed a traditional Filipino folk dance and chant. At some points, the piece cloaked him entirely; at others, it rested lightly on his shoulders like a fabulous cape, fanning out as he spun—sending the plastic-packaging fringe flying.

During the talk that followed, he explained that he altered the steps slightly so as not to offer the ritual up for consumption. The steps, the song, the traditions, the banígs themselves are sacred to Alan and represent a personal cycle of life and death.

“I was born on a baníg,” he said. “When my father was retrieved from the ocean, they wrapped his body in a baníg.”

Shortly after this performance—mere days actually—Alan hopped on a plane to the Philippines to begin his Fulbright study. There, he tells me, he’s continuing to approach his work with a spiritual sensitivity.

“I’m immersed in natural materials here, which I have been craving,” he said. “There is an area here—the province of Palawan—with abundant resources, and the tribe protects those resources. They have an almost ritualistic relationship with their materials. I’m not from that tribe, and I don’t want to co-opt their practices, so I’m developing my own approach to talking to the land and asking permission and offering thanks, drawing from the methods I learned in my childhood.”

He’s completed a number of new works, which he’ll be exhibiting at Real Art Ways in Hartford, Connecticut, in 2023. These new weavings maintain Alan’s trademark focus on material and color, but contrary to the controlled chaos that characterized his previous work, they are narrow and precise, with tight, cohesive patterns that unfurl like scrolls and are dotted by delicate organic ephemera. They capture a harmonious quality that speaks to an artist who feels complete, confident, and unconstrained.

“I feel so free here,” he said. “I’m not afraid of showing anything. Now, it’s about exposure, it’s about showcasing, and that’s showing up in the work.”

Alan is learning traditional Filipino weaving practices as part of his Fulbright scholarship. His new works (left: untitled woven baníg; right: detail) make use of those techniques and showcase the natural fibers of the region. Photos courtesy of the artist.

In a stark 180 from the internal tug-of-war that has underpinned his practice thus far, Alan plans to move forward in transparent generosity, going as far as to create narrative texts—in both Tagalog and English—that he intends to hang alongside the pieces. “I want to amplify that legibility and visibility; I want to offer everything—details, scholarship, materials, stories, and histories,” he said. “Right here, right now, I’m not hiding anything.”

My favorite of these new works, which is as yet untitled, is a long weaving of gentle tans and ochres banded by blue and striped with orange leaves that are as bright and fragile as saffron threads. Exquisite tendrils of wispy stems and dried blooms extend beyond its warp, and—even though I’m observing it through a screen—I know I’m in the presence of something sacred. My own response is bodily, and I can’t help but wonder how Alan will move on it, around it, with it in the future as an artist emancipated, free to make as he pleases.

Bhen Alan’s solo exhibition “Tago ng Tago (Hidden and Hiding)” is on view at Boston University’s 808 Gallery from November 3–December 1, 2022.