On August 11, 1973, Cindy and Clive Campbell (aka DJ Kool Herc)’s back-to-school party in the Bronx moved hip-hop out of gestation and into public space. Fifty years later, we’re witnessing hip-hop’s transition into middle age here in Boston. From Black Market’s Buy the Block Party 3, to BAMS Fest’s celebration of DJ Grandmaster Flash in Franklin Park, to the GLD FSTVL creating space for the music in front of City Hall, hip-hop’s 50th birthday continues to ring out.

One week after the officially recognized anniversary, Liza Quiñonez’s voice powered through DJ Mez.wav’s place-making set as she introduced us to Street Theory’s latest installation during the opening reception on August 19, 2023. Co-curated by Quiñonez, Chico Silvera, Pacey Foster of the Massachusetts Hip-hop Archive, and rapper Edo G.—the first Boston rapper to go number one on Billboard charts—“Hip-Hop: Seen/Unseen” is on view through November 15 at Dewey Square on the Rose Kennedy Greenway. Featuring historical and contemporary photography and ephemera, the exhibition represents a celebratory turn backwards and forward. It’s as much historiographical as it is creative, seeking to help write an often untold history of Boston’s hip-hop community.

Street Theory, a creative agency helmed by Liza Quiñonez and her artist husband, Victor “Marka27” Quiñonez, crafts a variety of productions that center communal and open approaches to viewing and creating works. Showing at the Greenway was a deliberate decision; Liza Quiñonez—who is also the City of Boston’s Transformative Public Art Mural Consultant—explained that it “transformed our exhibition into a public art piece. This is not tucked away in a museum or gallery; it’s out in the open, free and accessible to everyone.”

Installation view, “Hip-Hop: Seen/Unseen,” Dewey Square Plaza on The Greenway. On view through November 15, 2023. Photo courtesy of The Greenway Conservancy. Photo by: Corey Washington.

Panels of rare photographs and ephemera, organized into collections held by stanchions, fill a corner of the open plaza at the south tip of the Greenway. Situated in between the financial district, South Station’s burgeoning new development, and the towering Federal Reserve building, the exhibition dares to carve out space amongst the moneyed for an archive of working class Bostonian culture. In Quiñonez’s telling:

“The Boston hip-hop scene was a space where Black and Brown communities were sharing their histories and stories through the graffiti writers, MCs, b-boys/b-girls, and DJs who were creating out of pure love and passion for the music and culture—and it continues to be till this day. These were the spaces and experiences that embraced me and showed me the real heartbeat of this city. Assembling “Hip-Hop: Seen/Unseen” was my homage to this journey.”

Large contributions from other troves and tellers offered material and narrative support: the Massachusetts Hip-Hop Archive—housed and managed by the University of Massachusetts, Boston—and Chico Silvera’s personal collection of hip-hop event ephemera populate most of the outdoor showing.

Installation view, “Hip-Hop: Seen/Unseen,” Dewey Square Plaza on The Greenway. On view through November 15, 2023. (left) John Nordell, Disco P and the Fresh MC on Warren Avenue, Roxbury, 1985. (right) John Nordell, B-Town Battle at the Institute of Contemporary Art, 1986. Courtesy of The Mass. Hip-Hop Archive at UMass Boston. Photo courtesy of Pacey Foster of the UMass Hip-Hop Archive at UMass Boston.

Walking through the exhibition space, the local specificity felt enriching and refreshing. Much of rap’s sanctioned history-telling is exclusive to New York’s five boroughs, but “Seen/Unseen” challenges this narrative: New York is only referenced to offer context to developments in Boston. Geechi Suede, an emcee who performed in the ‘90s with fellow rapper Sonny Cheeba as the Bronx, NY-based Camp Lo, felt this emphasis at the event and shared with me that the showing stamped once and for all that “the contribution of Boston hip-hop is undeniable in elevating the culture.”

John Nordell, Young women with boombox in Downtown Crossing, 1986. Courtesy of The Mass. Hip-Hop Archive at UMass Boston.

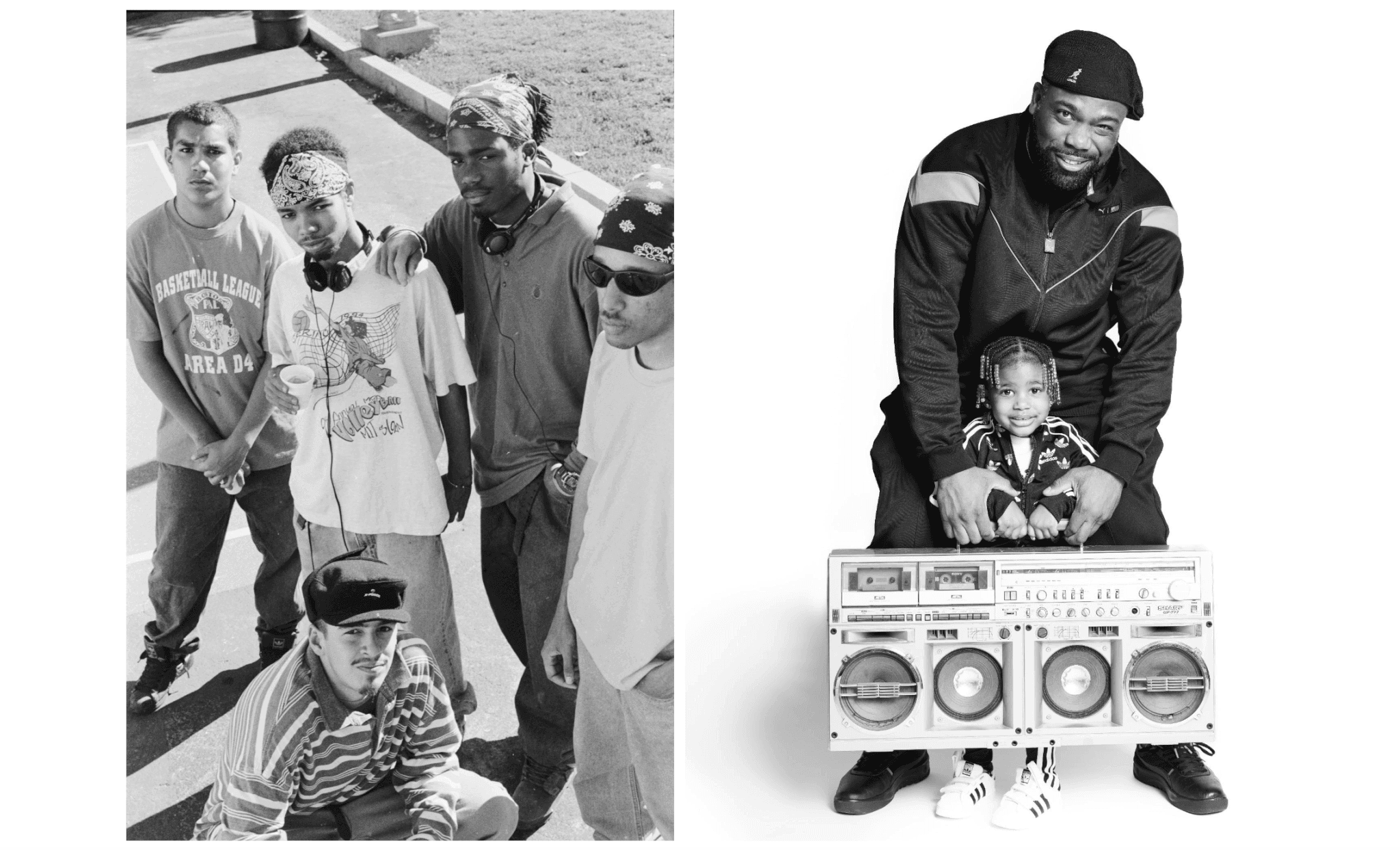

The street-facing collection of photos brings to the fore Black Bostonians enjoying the performance and playing of rap music. From folks hanging around outside of the foundational hip-hop radio show Lecco’s Lemma to a rhyme battle held at the old ICA/Boston firehouse building in Copley Square in 1986, ‘80s communal enjoyment expresses itself anew. The culture around the music grounds two more sets of photo panels from that period: a group posing in a bare tree with Adidas sneakers for leaves, some Dapper Dan-esque jackets belonging to the T.D.S. Mob, and members of the Floor Lords b-boy crew fill the backside of the collection.

John Nordell, Artists outside the Lecco’s Lemma Show at WMBR in Cambridge, MA, 1986. Courtesy of The Mass. Hip-Hop Archive at UMass Boston.

Graffiti and street art are a focal point of the exhibition. The set of panels furthest from the street celebrates graffiti, its crews, and its production. One panel shows two photos of Rob “ProBlak” Gibbs, one of Boston’s most well-known street artists, hanging around and getting a piece up at Peters Park in the South End; another panel showcases the FLY ID-ALA crew (including ProBlak and Marka27) and a mural they produced in New York. Quiñonez imparted that the show “stands as a testament to the genesis of [Street Theory’s] journey with graffiti and street art, all rooted in hip-hop.” Hip-hop generated a distinct visual language; hand-made and loud, this aesthetic from the undercommons is apparent not only in its graffiti but also in Silvera’s collection of promotional materials and flyers, which fill two panels.

SIDE Presents, aka Marlyn Urquiza (far left) and Therlande Louissaint (far right), hosted a panel discussion with (from left to right) Dart Adams, Lee Beard, Latrell James, Ashley Lord, and Allison Finney during “Sound In the City” at the Rose Kennedy Greenway on August 19, 2023. Behind the panel is DJ Mez.Mav spinning tunes. Photo courtesy of The Greenway Conservancy. Photo by: Corey Washington.

“Sound In the City,” an event organized by social justice educator Marlene Boyette, followed the opening. First on the docket was a panel moderated by local events and promotions duo SIDE Presents, aka Marlyn Urquiza and Therlande Louissaint. What unfolded was a who’s who of figures instrumental in telling hip-hop’s history, protecting its legacy in performance, and producing its soundtrack in real-time.

Dart Adams, a hip-hop historian, journalist, and fact-checker, proffered anecdotes drawn from his deep body of knowledge. According to Adams, when the documentary of graffiti culture titled Style Wars first aired on Boston’s PBS affiliate WGBH in 1983, young people tag-bombed the old Elevated Orange line trains en masse. In response, WGBH stopped airing the film, and rumors spread through his community that this decision was a result of the City of Boston’s opposition to graffiti. This resistance to Black and brown youth culture characterizes many of Boston’s interactions with hip-hop and reflects hip-hop’s often hostile relationship with governance. Immediately after the panel discussion, attendees filled a giant poster board on-site with names, tags, and throw-ups, excited to leave their mark and let it be known that they were here.

From the panel sprung an impromptu listening session, a memory path charted by muralist Lee Beard’s reflections on the art of sampling. DJ Mez.wav tuned us into “Inside My Love” by Minnie Ripperton and its offspring across the decades, from Tribe’s “Lyrics To Go” eighteen years later to J. Cole’s “Everybody Dies” another twenty years removed. Black passion oozed out of each record, tributes to Ripperton’s slyly coded song. The love was passed down generationally, like Black experiences intertwined across time: repetitive, yet distinct.

Breathe Life (2022) mural by Rob “ProBlak” Gibbs was the backdrop to “Sound In the City” at the Rose Kennedy Greenway on August 19, 2023. Photo courtesy of The Greenway Conservancy. Photo by: Corey Washington.

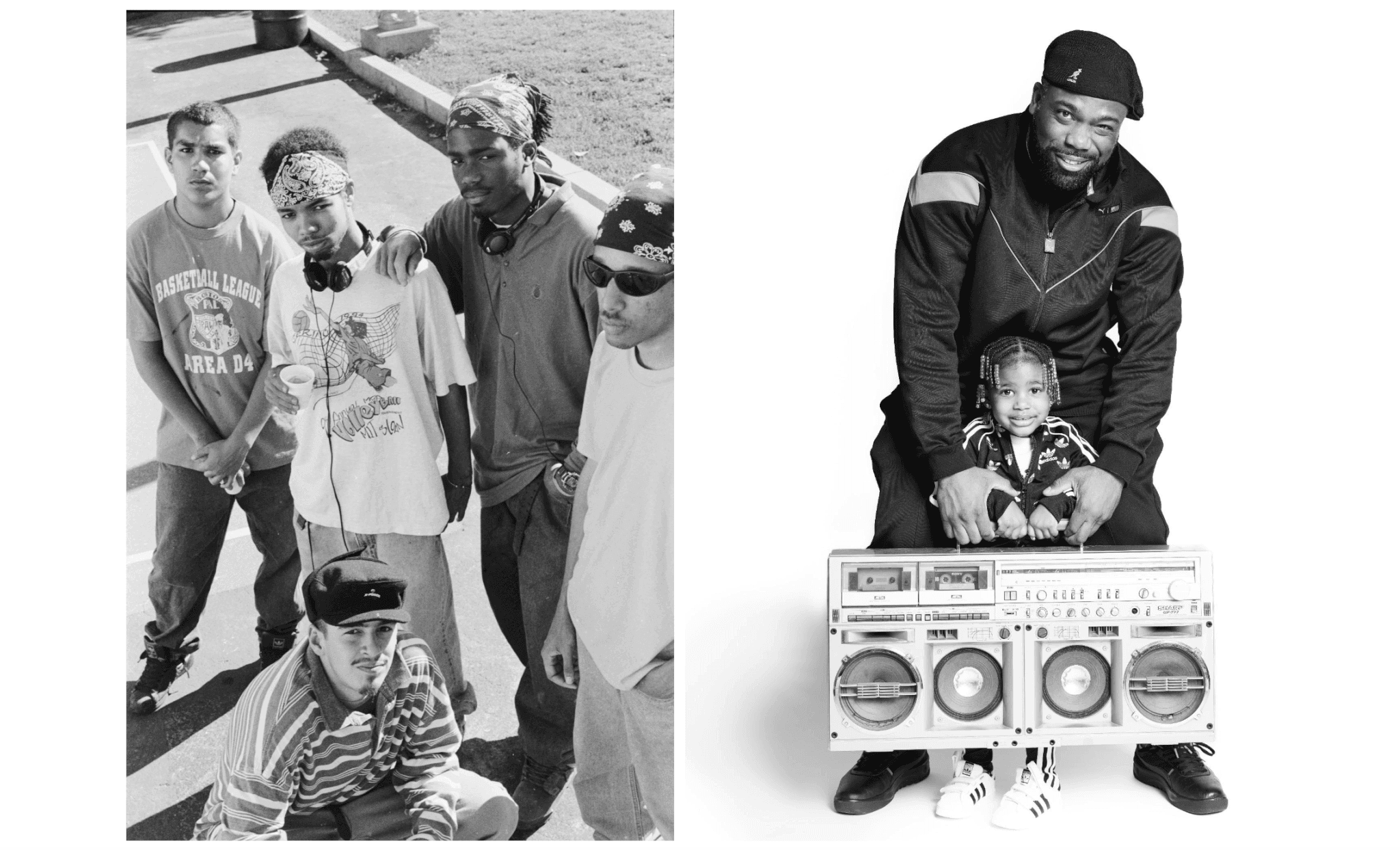

For Adams and Beard both, this celebration was more than just cultural history; it was their own lives reflected back to them. Adams shared that T.D.S. Mob, hailing from the South End, was his neighborhood’s rap crew and he used to practice b-boying with the Floor Lords. The Breathe Life Together (2022) mural Beard worked on with his mentor ProBlak as a member of the GN Crew stood directly behind their panel discussion. The final photo panel of “Seen/Unseen” is a photograph of ProBlak’s daughter Bobbi, Adidas’d-out and stepping on a boom-box, part of a photoshoot that generated the imagery for the mural. ProBlak himself two-stepped over to Beard as our interview wrapped.

(left) John Brewer, ProBlak, Rezume, FERB, Klue, 1995. Peter’s Park Handball Court, South End. Courtesy of John Brewer. (right) Gabriel Ortiz, ProBlak & Bobbi with Boombox, 2021. Breathe Life Together Photoshoot. Courtesy of Gabriel Ortiz.

Adams’ last history lesson centered the power of hip-hop as a tool for social change, chronicling how Bronx gangs politicked to create peace, and set the stage for hip-hop’s birth. In his words: “What these people were doing was activism.” It was a revolutionary act to spread joy, love, and unity. Hip-hop affirmed self-belief, enabling community members to feel like, “[they] can write, [they] can build community], [they] can change the law from a hip-hop perspective,” said Adams. Hip-hop isn’t just something you listen to—it’s something you do, and the organic intellectuals hip-hop produced sought action through cultural production.

A dance performance and battle broke out after the panel. Folks of all ages uprocked and power-moved across a small platform, including original and new members of the Floor Lords. Familiar shouts, emphatic hugs, and enthusiastic daps rang out all afternoon. Present-day Boston artists and creatives showed out: MFA artist-in-residence Rob Stull, rapper and poet Rafael A. Shabazz, and singer Miranda Rae made the rounds, as well as hip-hop and community event coordinator Stephen Lafume, locally known for co-organizing Thrill. The revolution in motion was in full-effect, counting all of us among its participants.

More than anything, the opening of “Hip-Hop: Seen/Unseen” and “Sound In the City” underscored that memories don’t live like people do, but we can bring them back to life by excavating and showcasing a people’s archive.

Live artwork by Curtis Williams at “Sound in the City.” Photo courtesy of The Greenway Conservancy. Photo by: Corey Washington.

“Hip-Hop: Seen/Unseen” is on view at Dewey Square Plaza on The Greenway through November 15, 2023 as part of The Greenway Public Art Program.

Alula Hunsen is an essayist and research assistant based in Boston. From trends to transit, you can find his work here.