From March to June this year, the 2024 Emerging Boston Art Writing Fellows have participated in an arts writing intensive with Boston Art Review (BAR) and Praise Shadows Art Gallery. Week to week, they engaged in a variety of workshops with industry professionals—editors and freelance writers; arts and publishing nonprofit leaders; scholars, museum educators, and civic servants—to find their voice, sharpen their craft, and explore career paths in the arts. Along with working hands-on at Praise Shadows Art Gallery and BAR, the fellows also visited and toured multiple art spaces—from artist studios and nonprofit galleries to commercial galleries and university museums—with the goal of immersing themselves in Boston’s art community, familiarizing themselves with the various places that steward art, and encountering artists at work here.

While the fellows have honed their art writing skills by publishing collaboratively in our latest print issue and individually online, a major aspect of their writing this semester was practicing one of the shortest forms possible: the paragraph. During three site visits, the fellows were tasked with selecting an artwork that struck them and writing a paragraph about or alongside it. Most of this writing took place at the art space itself, as the fellows pulled out their journals, sat down, and immediately wrote about what they just saw. Then, they shared it aloud and received feedback from each other. As the fellows currently work on their final projects, this fellows blog documents the behind-the-scenes of their art writing journey with us this past semester. This blog is also a shout-out to some of the artists and spaces that have cultivated our work throughout the program.

At Northeastern University Gallery 360, director and curator Juliana Barton gave the fellows a tour of “Fluid Matters, Grounded Bodies” and shared how she puts group exhibitions together from a museum education perspective as a university gallery curator. Then, the fellows headed to the Mills Gallery at the Boston Center for the Arts where Julia Szejnblum, associate director of exhibitions, discussed the inner workings of an arts nonprofit and BCA’s distinctive 1:1 curator and artist pairing program, followed by a tour of “Duty-Free Paradise,” a momentous survey of Lani Asunción which resulted from this initiative. At the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston, assistant curator Tessa Bachi Haas conducted a walkthrough of “Firelei Báez” from the perspective of curating and installing a large museum survey exhibition with a preeminent contemporary artist. Below, you will find the fellows’ initial reflections on artworks that moved them.

Boston Art Review is supported through the BAR Giving Circle. Programs like this are made possible with support from art_works, Boston Center for the Arts, Boston Cultural Council, the Wagner Foundation, and Mass Cultural Council. If you’re interested in learning more about how to support this program, please contact Jameson Johnson.

Fluid Matters, Grounded Bodies

November 16, 2023–April 6, 2024

Northeastern University Gallery 360

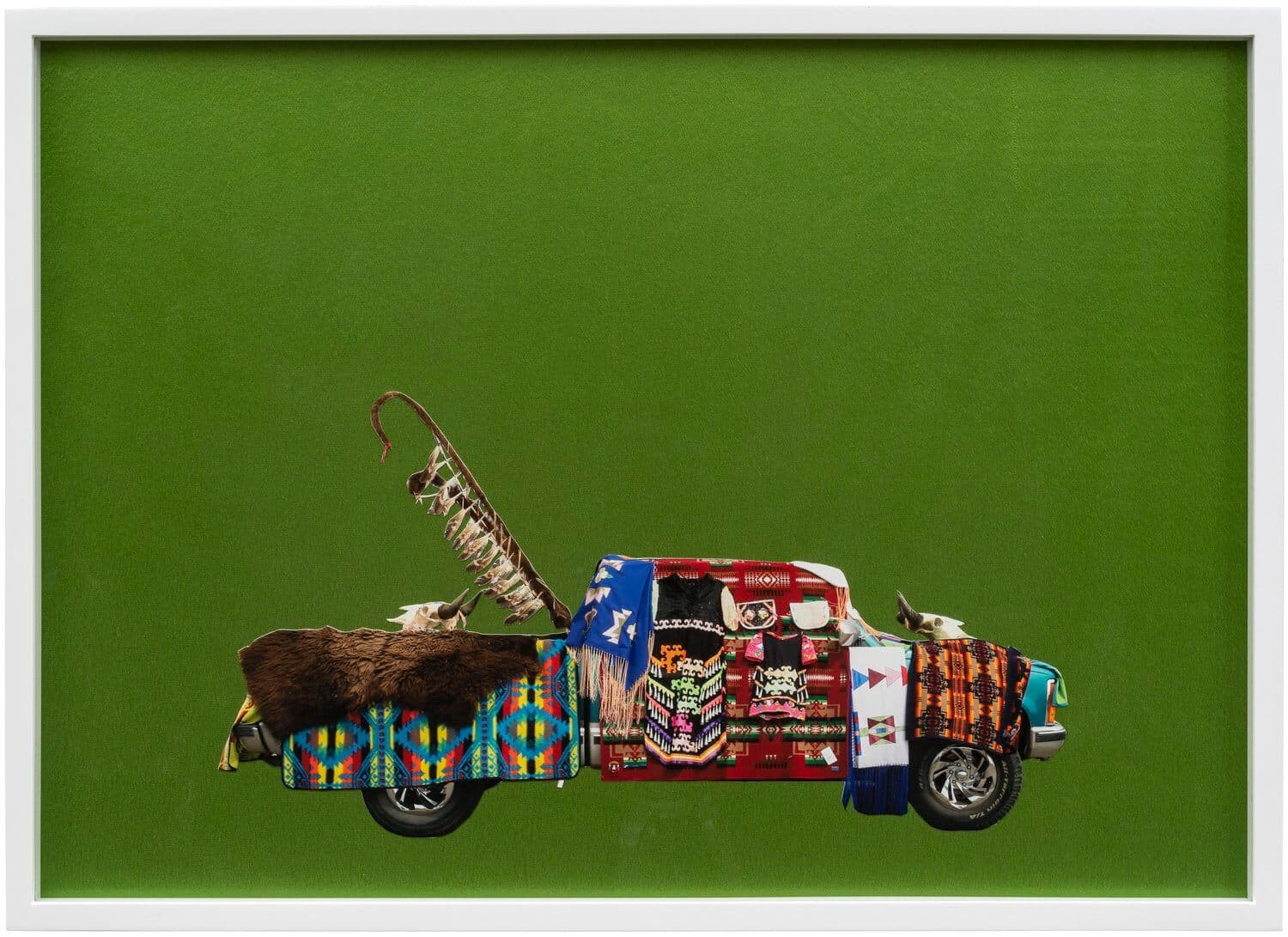

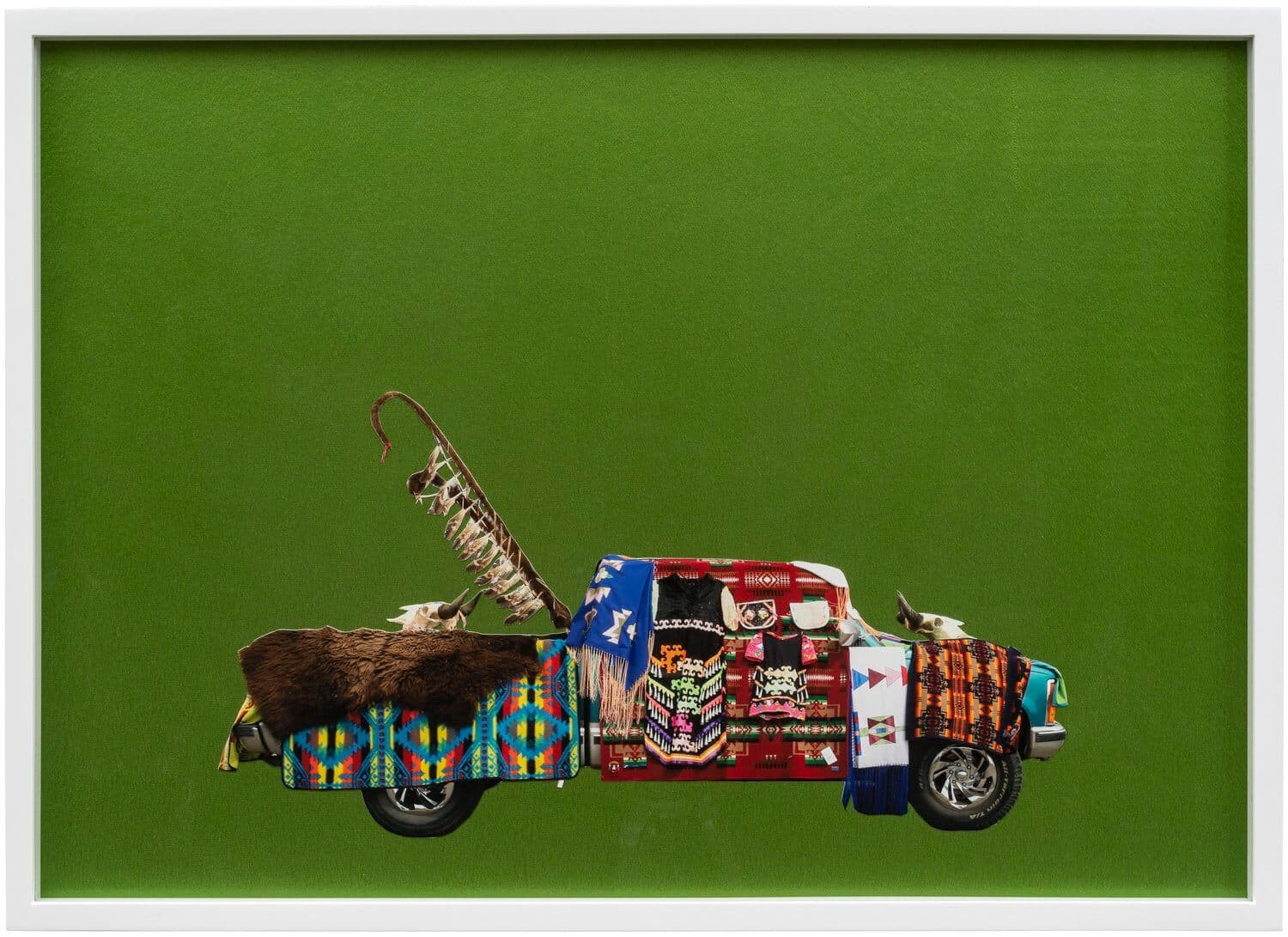

Wendy Red Star, A Float for the Future, 2021. Fabric with archival pigment photograph. Courtesy of a private collector.

Wendy Red Star’s A Float for the Future (2021), featured in the “Fluid Matters, Grounded Bodies: Decolonizing Ecological Encounters” exhibition at the Northeastern University Gallery 360, consists of four successive images of a truck steeped in Native American (Apsáalooke) regalia. The vehicles—typically horses in the traditional Crow Fair parade this work reimagines—are long, spacious, and the types often seen toting American flags. However, make, model, and the drivers themselves are obscured by colorful textiles overwriting conventional American touchstones. With each depiction, Red Star—by reclaiming aspects of a culture that has historically marginalized her own—presents a middle ground between Indigenous traditions and the ingenuity required for their preservation.

—Erwin Kamuene

Ada M. Patterson, Yuh Too Sweet, 2018. Digital video, 3 minutes and 54 seconds. Courtesy of the artist.

At just three minutes long, Ada M. Patterson’s Yuh Too Sweet is an audiovisual treat offering motifs such as exploitation of the land and historical memory. Upon putting on the gallery headphones, viewers are immediately met by the sound of a boiling, bubbling substance. This sound is paired with a superimposed visual of ocean waves crashing against fields of sugarcane, with granules of brown sugar replacing the beach’s shore, suggesting the crop’s overtaking of the landscape. Eventually the landscape is encroached by another industrial cash crop—tourists. Following their arrival, the ocean then transforms into the simmering, sticky, brown substance that is the cane syrup alluded to from the very beginning. The poetic prose that appears throughout in garish white text describes the parasitic arrival of both.

—Helina Almonte

“Lani Asunción: Duty-Free Paradise,”

January 20–April 13, 2024

Mills Gallery, Boston Center for the Arts

(left) Lani Asunción, Blood, Bones, Aloha!, 2024. (right) Lani Asunción, Dole House (Self Portrait), 2021. Installation view, “Lani Asunción: Duty-Free Paradise,” Mills Gallery, Boston Center for the Arts, 2024. Photo by Melissa Blackall. Courtesy of Boston Center for the Arts.

The hard part about Lani Ascunción’s BLOOD, BONES, ALOHA! (2024) featured in “Duty-Free Paradise” —their retrospective exhibition at the Mills Gallery at the Boston Center for the Arts—is trying not to trip over it. Moreover, tracing your feet along its outline as you attempt to discern the writing emblazoned across the surface. The piece is a small mesa of sand that gently slopes at the edges, creating the effect of a ruin or something aged beyond recognition. It requires you to adjust yourself in a manner that ironically turns viewer into spectacle, despite or because of the work’s simplicity. The message inscribed is similarly constructed to ensnare the viewer’s biases. Distilled from the memoir of Hawaii’s last monarch, Queen Lili‘uokalani, the phrase “Blood, bones, aloha!” ostensibly evokes the violence of colonialism. But as the broader quote suggests—“My love for my homeland and my beloved people, the bones of my bones, the blood of my blood! Aloha!”—the words are equally a radical declaration of a love so potent it seeps into the viscera of a people, and as the work conveys, is sown within the land itself.

—Erwin Kamuene

Fellows Helina Almonte and Erwin Kamuene during a visit to “Lani Asunción: Duty-Free Paradise” at the Boston Center for the Arts, February 2024.

Lani Asunción’s solo exhibition “Duty-Free Paradise” offers viewers a striking self-portrait. Cloaked in piña fibers and military survival cords, we see the artist seated in front of a vanity. Although Asunción’s back is turned, their face is photographed through the mirror’s reflection. Their clenched fist and locked gaze insinuate that someone has interrupted her sitting. There is an interloping voyeur who presumably is you. But your attendance does not embarrass the artist; this space they inhabit is their right. Hawaii is long known as an optimal tourist destination for its natural beauty and tropical climate. What is often left out of the perfect Instagram vacation photo is a crucial aspect of Hawaii’s history—the United States’ violent use of military force and colonization. The islands’ natives live with these histories at the forefront of their lives; they haven’t had the privilege to forget. Asunción’s gaze rejects this notion by locking eyes with the folks who try to look past and deny their existence. Using the mirror to execute an optical trick, they force the viewer to face their reflection and in turn, they must look her in the eye—existences and reflections intertwined.

—Helina Almonte

Installation view, “Lani Asunción: Duty-Free Paradise,” Mills Gallery, Boston Center for the Arts, 2024. Photo by Melissa Blackall. Courtesy of Boston Center for the Arts.

In “Secret Stations: Bango 720740,” Lani Asunción implicates us, the viewers, with a reminder that as Americans, we too have contributed to the erasure of native Hawaiians and the violence that propels the United States’ colonization process. The caution-tape-yellow flag hangs horizontally from a gold flagpole, and this metallic impermeability calls back to the military occupation of Hawaii. In the center stands a boldly printed pineapple, almost ominous, surrounded by a maze created to entertain visitors at the Dole plantation, which emerged as a US corporate enterprise after the overthrowing of the Hawaiian government and sold pineapples as exotic, commodifying Native Hawaiian values. Asunción took the map of a scavenger hunt within the maze for children and shows the eight targets in the same scarlet as the number of the tour she took when she visited, 720740, at the bottom. On the back of the flag, the words “BLOOD, BONES, Aloha!” cast shadows through the fabric—the reality of the plantation showing through the “fun” facade. As we take this in, Asunción turns the act of searching back onto us, forcing us to complete the scavenger hunt and replicate the experience of tourists to the plantation. Although we stand in Massachusetts, after being endowed with the ticketed number at the bottom and seeing the video tour of the plantation, we feel as if we are also arriving at the plantation, participating in the violence involved. As the flag towers over us, it reflects the nature of the plantation: overshadowing native Hawaiians and remaining as a reminder of its dark legacy.

—Dylan Bunyak

“Firelei Báez”

April 4–September 2, 2024

Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston

(left) Firelei Báez, On rest and resistance, Because we love you (to all those stolen from among us), 2020. Oil and acrylic on canvas. 48 × 60 inches (121.9 × 152.4 cm). Private collection. Installation view, “Firelei Báez,” the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston, 2024. Photo by Mel Taing.

The paintings of Firelei Báez often give the impression of a double exposure or an intricate tableau jolted out of alignment. As seen in On rest and resistance, Because we love you (to all those stolen from among us) (2020)—her depiction of a woman reading and lounging on a bed of grass—it’s easy to spot the eye partly occluded by the bundle of flowers clouding the subject’s face. However, her face is beside the point. By pushing her representation just short of abstraction, Báez explodes her subject into a texture collage, unveiling a richness that overwhelms our ability to quantify it. The garland of baby’s breath Minnie Riperton sported is the same tiara this woman wears. The yellowed pages of Octavia Butler’s dystopian novel Parable of the Sower are signs of age, neglect, or both. More than making us question who we are, Báez excels at making us wonder about the traditions that shape who we are and the importance of honoring and preserving them.

—Erwin Kamuene

Can I Pass? Introducing the Paper Bag to the Fan Test for the Month of July (2011), is a calendar year’s worth of self-portraits whose features have been reduced to silhouettes in varying shades of brown, allowing for only the eyes to be seen. The lack of features is not due to a lack of skill—the piece appears as part of a survey of over fifteen years of Firelei Báez’s work. The veiling of the face can be ascribed to the concept of opacity—the intentional covering of a subject’s face to conceal their identity and to pay homage to the complexity of the figures being imaged. Báez employs this strategic rendering in several of the bodies that appear in her work—in this case, giving herself the same amount of grace. In this specific instance, Báez’s complexity is tracked through the color of her skin and its varying shades of brown throughout the hottest month of the summer, July. Through measuring her skin tone by the brown on the inside of her forearm, Firelei references the paper bag tests that appeared throughout the Jim Crow Era. If their skin was darker than a brown paper bag, Black people could be denied entry into certain social gatherings. The inside of the wrist was often used as a reference point in the case that the person in question used makeup to lighten their skin in order to “pass.” Firelei places herself within the context of these histories, displaying how something as simple as having a tan from one day to another may mean being considered “too dark” to pass into spaces you would have been allowed into only days prior. Can I Pass? Introducing the Paper Bag to the Fan Test for the Month of July points the finger at the absurdity of these dated practices and champions the versatility and resilience of the African diaspora, reminding us that any attempts to typify the “right kind” of Blackness are wholly impossible.

—Helina Almonte

Firelei Báez, Adjusting the Moon (The right to non-imperative clarities): Waning, 2019–2020. Oil and acrylic on panel. 114” × 78” × 1 ½” (289.6 × 198.1 × 3.8 cm). Installation view, “Firelei Báez,” the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston, 2024. Courtesy Shah Garg Collection.

One of two installations in Firelei Báez’s newest show at the ICA / Boston, the “mirror room” offers a confronting viewing experience for Adjusting the Moon (The right to non-imperative clarities): Waxing and Adjusting the Moon (The right to non-imperative clarities): Waning (both 2019–2020). Behind thick curtains, museum-goers step into a low-lit, narrow space with reflective walls and the two large paintings mounted on opposite ends. Both are composed of arched frames that fail to enclose their subjects: standing figures obscured by textured fireworks of color. The positioning forces viewers to face one piece at a time, and to see themselves repeating infinitely, inescapably, all around them. There comes a sudden feeling of embarrassment, almost a feeling of offensive exposure as the mirrors create a 360-degree view, and concurrent feelings of jealousy toward Báez’s subjects who receive the contrasting kindness of anonymity. Although the paintings appear similar, important differences reveal themselves with time. The title, a reference to the portion of the lunar cycle where the moon shifts into shadow appearing to get smaller, the Waning piece is more reserved, the figure’s feet firmly within the bounds of the frame, and its corresponding bursts of color made up of straight lines and clear strokes. Facing it, the Waxing piece is bolder—its explosion of color more free flowing. This figure steps forward into its future, left foot toeing the line of the painted frame, and the paint is freed, utilizing Báez’s distinct pouring technique. Unless the viewer chooses to meet their own reflection, they must decide which piece to turn to, which path to explore. This quiet moment of introspection counters the public nature of the rest of the survey, providing a brief pause before the exhibition climaxes in the second installation, A Drexcyen chronocommons (To win the war you fought it sideways) (2019).

—Dylan Bunyak

Learn more about the emerging art writing fellowship program.