When the French-born, Harlem-based artist Elizabeth Colomba starts an oil painting, she does so like the masters, beginning with the grays of an underpainting, slowly building up color and texture on eighteenth-century petticoats and patterned wallpaper until she’s left with the final details: the delicate tatting of a lace cuff, the tiny scarlet feathers of a cardinal’s wing, or the light glimmering around a cloud of black curls. At “Mythologies,” her solo show at the Portland Museum of Art, we’re invited to do the same, first by identifying the story that informs the work (her titles typically hold clues) and following the breadcrumbs she’s left along the way in fabrics, furniture, and animal familiars until we’ve fully entered her world, one populated by resolute and magnificent Black women inhabiting the stories they’ve been violently written out of.

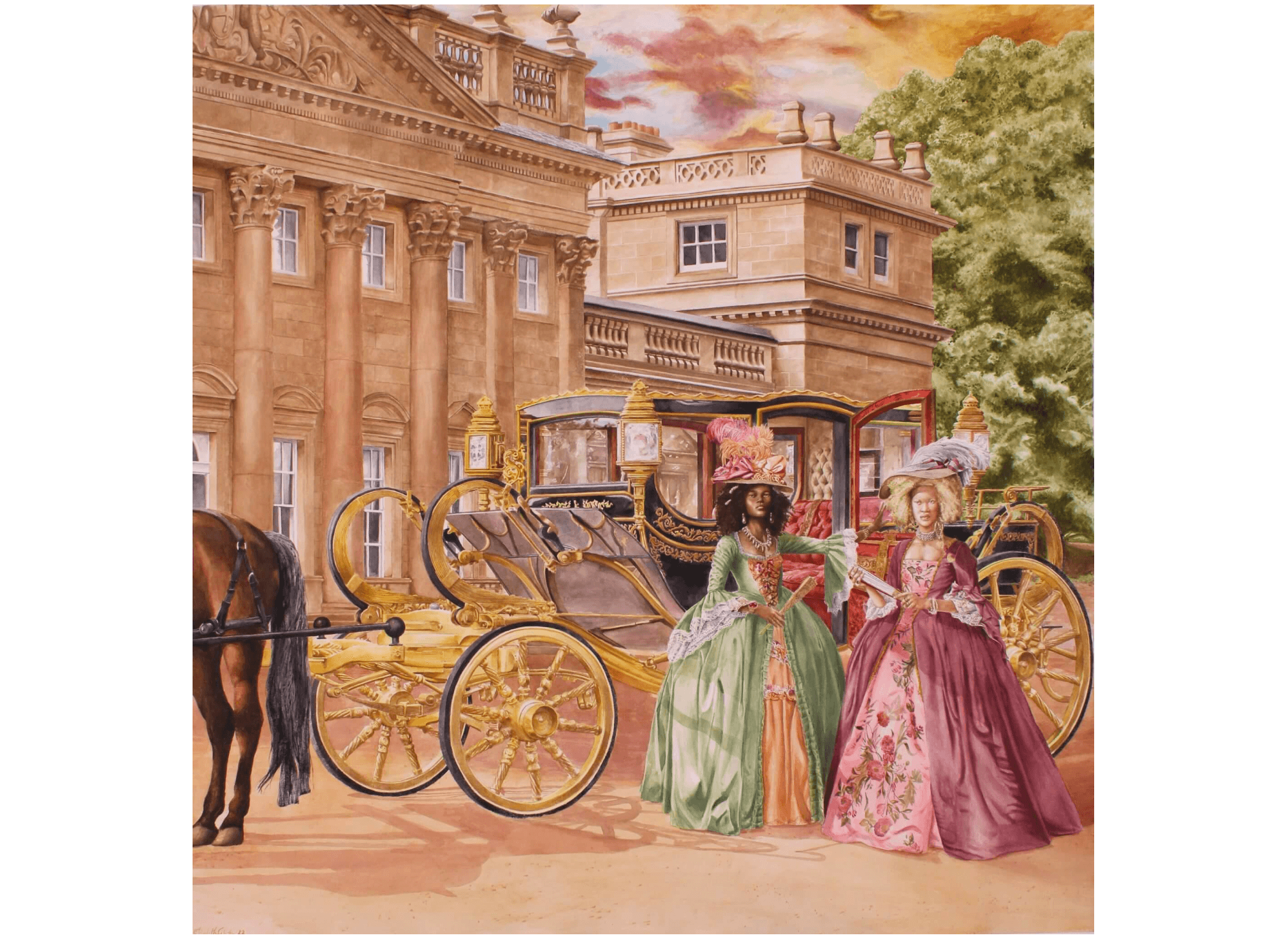

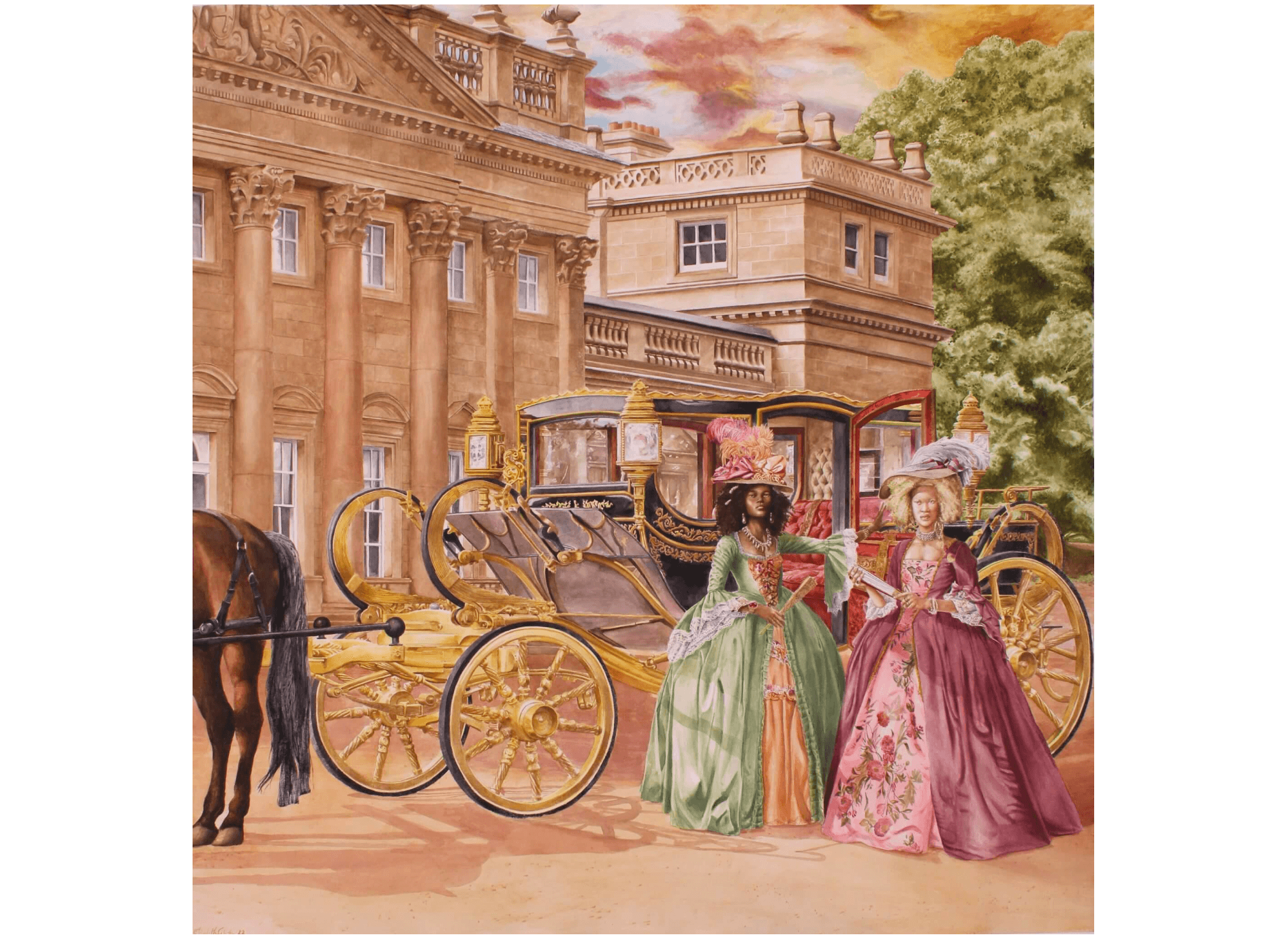

Primarily a painter—though her first and only film, Cendrillon (2018), is also on view—Colomba classifies her work across four categories: historical, allegorical, feminine sacred, and mythological. While the title of this show may lead one to believe curators Monique Long and Shalini Le Gall would focus on the final lot, only Arachne (2009), The Reading (2014), and Study for Minerva (2022–2023) strictly allude to myths. Even Cendrillon, a retelling of the Cinderella story titled after Jules Massenet’s 1899 opera (the film was commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera), is technically a fairy tale, lacking the etiological undertones required of myth. The paintings garnering the greatest amount of real estate—her celebrated quadriptych of the four seasons in oil, or Harewood House (2022–2023), a remarkable feat of watercolor at 50″ by 40″—fall into her allegorical and historical categories, respectively.

Elizabeth Colomba, Harewood House, 2022–2023. Watercolor on paper, 50″ x 40″. Courtesy of the artist.

Instead of depicting myths, Long and Le Gall have created an exhibition about the process of constructing them. The entryway is papered with the shot list for Cendrillon, offering a behind-the-scenes look at the making of the short film and a nod to Colomba’s time in Los Angeles working as a professional storyboard artist. That narrow hallway leads you into a nearly enclosed single room, the Four Seasons (2012–2018) greeting you along the back wall, Cendrillion looping on the opposite, and finished paintings—all oil with the exception of Harewood House—hung alongside studies in graphite, white chalk, ink, and gouache.

By privileging a step-by-step approach to both art and myth-making, “Mythologies” elucidates the mechanics of Colomba’s practice, one where every detail is considered and every choice is rife with meaning. From the subjects—whether real or legendary—to the models (typically people she knows) to the inclusion of specific rooms, flora, fauna, and clothing, each painting is an amalgamation of references that serve to rescue Black women from the footnotes of history and reposition them in the world’s most powerful spaces, centering them in the narratives that underpin modern society.

Installation view of “Mythologies,” at the Portland Museum of Art. On view until September 3, 2023. Photo courtesy of the Portland Museum of Art.

The Four Seasons provide some of the most personal examples of her layered technique. Ordered from Spring through Winter, each six-foot-tall vertical painting features an elegant Black woman, her age, garments, and surroundings signifying her prescribed period. Composed using traditional methods learned at the École Estienne and École des Beaux-Arts, the works hark back to the portrait painters Colomba has listed repeatedly in interviews as inspirations: here we see the Baroque opulence of Velázquez and the soft edges of Sargent. Though curator and critic Dodie Kazanjian points out in the show’s accompanying audio that Colomba’s decision to personify the seasons (especially as women) is unusual, they call to mind a similar series by Alfred Stevens on view at the Clark Art Institute. Which is not to say that they’re equal in metaphorical potency or even visual impact. Stevens’s uniformly young society ladies, commissioned by King Leopold II of Belgium, are flouncy and frozen; his Spring blonde remains stiffly posed and gazing neatly into the distance while Columba catches her adolescent heroine—modeled after her own niece—gathering roses, arm outstretched, feet bare, chin tipped up in absorption to her task, the flowers crowning a tumble of curls.

Elizabeth Colomba, Four Seasons: Winter, 2012–2018. Oil on canvas, 72″ x 36″. Courtesy of the artist.

Those willing to work at uncovering the hidden messages in Colomba’s pieces will be especially rewarded with Winter (2012–2018). Here, we find a regal and contemplative older woman, the artist’s mother, dressed in a silk gown based on an early eighteenth-century mantua held at the Met. There are references to her native Martinique in the Caribbean scene by Winslow Homer above the fireplace and the traditional madras headdress crowning her coiled hair. A figure of wisdom and determination, she hugs a book with her right hand and, with her left, grips a gleaming wooden cane, the brass tip of which pierces through a giant crab—a symbol of the cancer that she suffered from while posing for the piece, having beaten it twice before. Colomba’s mother died soon after, but she saw and loved the painting. In it, she is self possessed and straight backed, her eyes focused up and away as if considering what’s to come.

“Mythologies” demonstrates the disciplined way that Colomba crafts narrative and artistic interventions, but it’s important to stress that the paintings delight at a surface level. Saturated in rich colors and imbricated with intricate patterns, they feel abundant and lush, an experience the artist reinforces by sharpening and softening the focus throughout, a crisp pleat here, a warm glow there. Each piece is grand in scope and scale, painted in a highly classical manner that requires the viewer to step back to fully appreciate it. Which, in this particular space, isn’t always easy. There’s simply not enough room in the small darkened gallery to take in the work to its full effect. I found myself wishing for just a bit more light and a bit more space, for both me and the women suspended around me, to breathe.

Visitors watch Elizabeth Colomba’s short film Cendrillon (2018) at “Mythologies,” on view at the Portland Museum of Art until September 3, 2023. Photo courtesy of the Portland Museum of Art.

Casting a light on forgotten women, inserting them into extravagant and airy spaces—this is what Colomba’s practice is all about. In some cases, she’s offering ease and power to real people, such as with Tricked Out in a Gay and Fashionable Finery (2022), a portrait of Harriet P. Jacobs, an enslaved couturier who escaped sexual abuse and brutality by living in a crawl space for seven years. In others, she’s reimagining legends that differ from the most commonly associated tales, but are in some ways truer to the originals. Take Cendrillon, for example. In Colomba’s film, we have our princess in the stunning South Sudanese model Grace Bol and a fairy godmother played by Colomba herself, who, rather than waving a wand, paints the scene captured in The Reading on the train of a blood-red gown. We have the stroke of midnight and the lost shoe. Though small details are lusciously and evocatively altered, the touchstones of the piece stay true to the story we’ve come to know through Disney’s blonde in blue and the Charles Perrault tale it was based on. Still, if recent Hollywood live-action adaptations are anything to go by, presenting a Black heroine when a white one is expected is a radical statement all on its own, one that’s likely to be met with cries for “authenticity.”

And that’s the point. This film—as with the rest of the work in “Mythologies”—exposes that outrage for the racist essentialism that it is. Whether they are ancient legends of wrathful gods or more recent accounts inked into our history books, myths have no authenticity. They are accretions of details painstakingly rendered and purposefully omitted; they reveal where the spotlight shines a halo and where it casts a shadow. Which brings us back to Cinderella. Rather than a Grand Siècle, mouse-driven carriage ride, the oldest attested rendition of the fairy tale comes to us from first-century Greece and features an Egyptian pharaoh who leads a great search to find the owner of a slipper that was dropped onto his lap by an eagle (it belonged to an emancipated courtesan named Rhodopis). No blond prince, likely no blonde princess either.

The stories that explain and inform our society are not immutable, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t vitally important. With “Mythologies,” Colomba recasts Black women into the starring roles of narratives where they find safety, influence, recognition, and rest, empowered protagonists of more expansive histories.

Elizabeth Colomba, Study of a Face, 2009. Watercolor on paper, 7.5 x 9.5″. Courtesy of the artist.

“Elizabeth Colomba: Mythologies” is on view at the Portland Museum of Art through September 3, 2023.