The UN estimates that one in seven people on this planet is a migrant who “moves by choice or by force.” This statistic appears on the opening wall text of “When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art,” a timely, trenchant exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art that’s embedded with a number of facts that bear repeating, as well as other less-quantifiable truths. Take the truth at the heart of “Home,” a poem by Somali-British writer Warsan Shire that lends the show its name and upends the notion that migration is ever entirely by choice. “No one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land,” Shire reminds us. “You only leave home when home won’t let you stay.”

The exhibition collects more than forty works by twenty artists from a dozen countries, all created since the turn of the millennium. Some take a big-picture approach. Covering a whole wall in the first room of the exhibition, Reena Saini Kallat’s “Woven Chronicle” (2011-19) draws on data to trace global movements of migrants and labor. Hand-woven in a chain-link pattern, her brightly color-coded map of the world makes an immediate impression, but closer inspection reveals that the skeins of yarn linking countries are in fact electrical wire. It’s a conduit that connotes both connection and division, since some is twisted to resemble barbed wire (a material that has proliferated in the artist’s native India since the 1947 partition that fractured her family).

Camilo Ontiveros, Temporary Storage: The Belongings of Juan Manuel Montes, 2017. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Museum purchase funded by the 2017 Latin American Experience Gala and Auction. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA © Camilo Ontiveros

Other works home in on an individual’s story with devastating specificity. That’s the case for Camilo Ontiveros’s sculpture “Temporary Storage: The Belongings of Juan Manuel Montes” (2017), in which rope binds a bed and a rolling chair, a mirror and a picture frame, a rainbow’s worth of karate belts and a pair of boxing gloves, among other personal possessions. Montes is believed to have been the first DACA recipient deported during the Trump administration, and these are the belongings he left behind, assembled by the artist with the permission of Montes’s mother. Perched on a sawhorse, the bound bed is upturned, slightly tilted, towering, and a little precarious. The ordinary yet particular nature of these objects lands like a punch to the gut.

Found objects also appear in “Border Cantos,” a collaboration by photographer Richard Misrach and composer/artist Guillermo Galindo. Misrach’s photographs of the Mexico-US border include a wall-spanning series of images depicting the detritus left by migrants’ travels: a bike, a belt, a single shoe, a Spanish edition of the New Testament, a water bottle painted black so it won’t reflect light, a scrap of clothing bearing an American flag. Captured in California and Texas, these artifacts are framed by patches of harsh terrain—scrubland, cracked earth, desert sand—and arranged in a grid that brings to mind an archaeological site, or maybe a crime scene.

Richard Misrach, Artifacts found from California to Texas between 2013 and 2015 / Artefactos encontrados entre California y Texas de 2013 a 2015, 201315. From the series Border Cantos, 2004-16. Courtesy the artist; Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York; Frankel Gallery, San Francisco; and Marc Selwyn Fine Arts, Los Angeles. © Richard Misrach

Installation view, When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2019. Photo by Mel Taing. © Richard Misrach and Guillermo Galindo

While Misrach documents debris, Galindo transforms it. His sound sculpture “Ángel Exterminador/Exterminating Angel” (2015) reimagines a piece of the Mexico-US barrier as a musical instrument, bringing lightness to weighty materials made heavier by history. Before it was deployed at the border, the twisted hunk of metal at the center of the work served as a helicopter landing strip during the Vietnam War. Now it’s a gong suspended from a repurposed drag chain, used by Border Patrol to sweep away the day’s old footprints so they can better track new ones. It all hangs from a gallows-like scaffold of wood blocks used in the construction of the border barrier.

LGBTQI refugees narrate their own harrowing journeys across borders in Carlos Motta’s video installation “The Crossing” (2017). Screens bring viewers face-to-face with people like Butterfly, a trans woman from Syria who first fled to Turkey, then made the perilous voyage to Greece on a small boat bearing nearly sixty souls, including a dozen children. Traffickers threw most of their belongings into the sea, but she managed to hold on to her compact mirror and used it to signal to the Greek coast guard. Butterfly eventually made it to the Netherlands, a destination she’d seen in movies and dreamed about, only to end up in a prison-like detention camp where one of her fellow refugees died by suicide. Meanwhile, Richard Mosse’s three-channel video “Incoming” (2014-2017) affords haunting views of such refugee camps, produced with a military-grade heat-vision camera designed for the battlefield and long-range border enforcement.

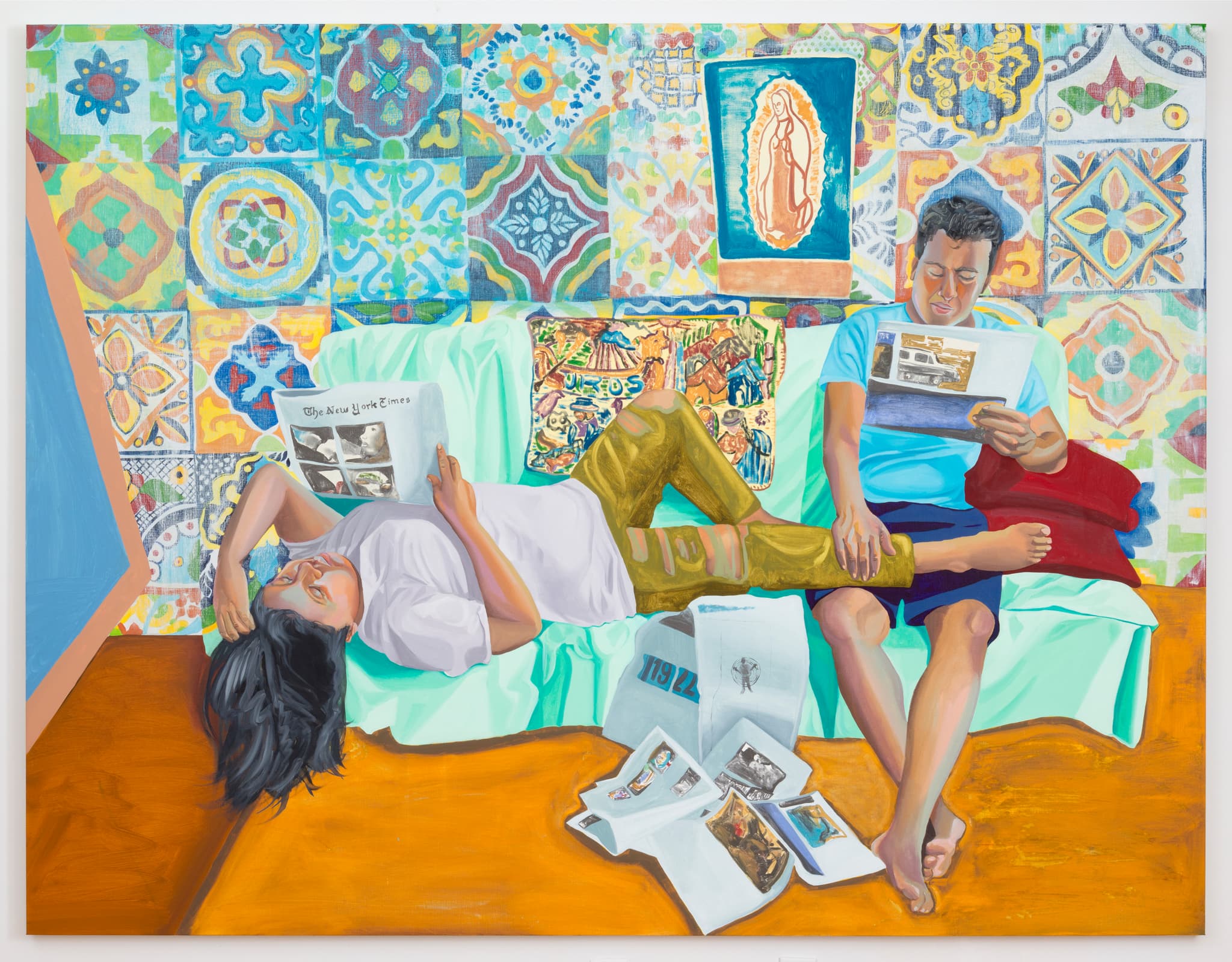

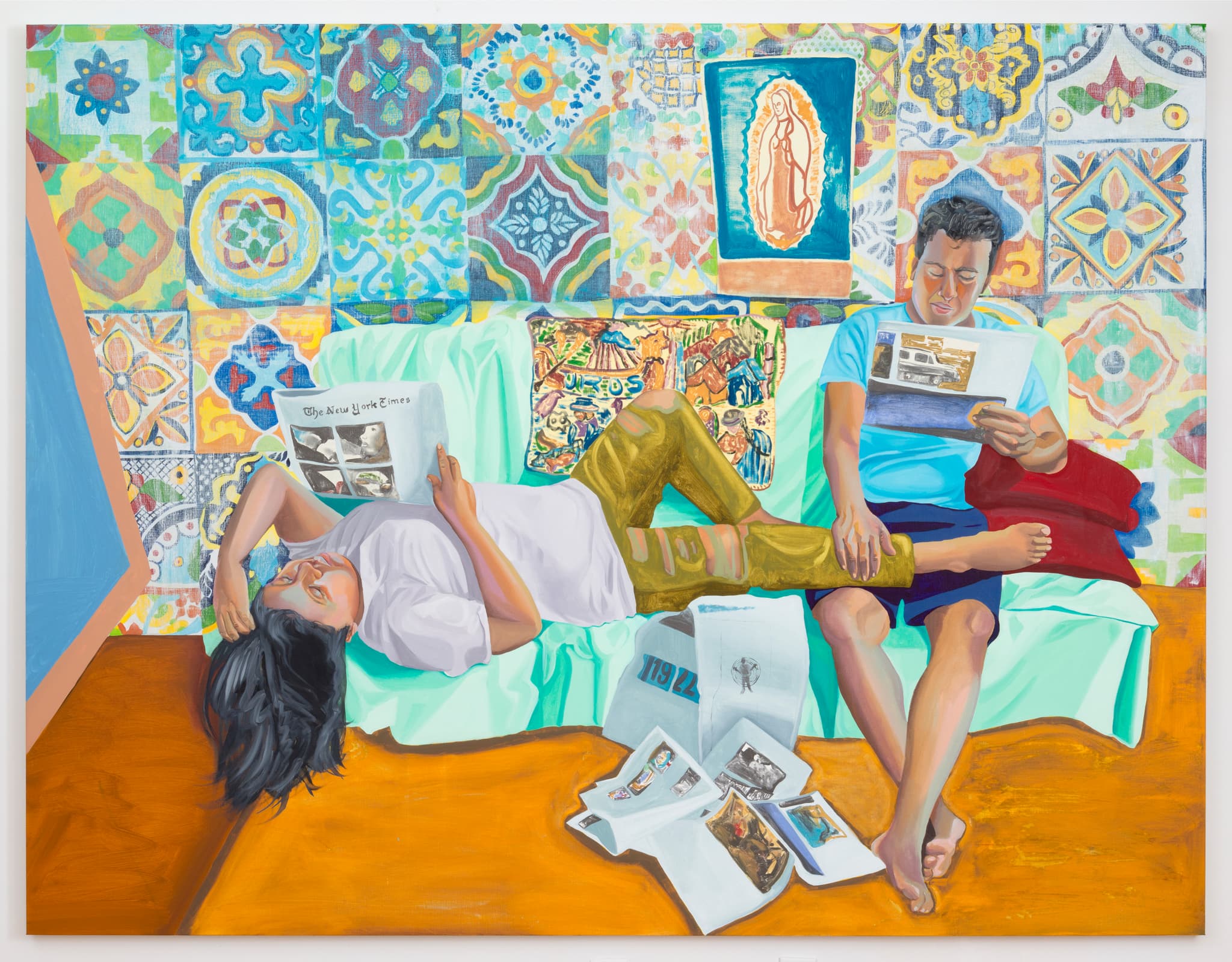

Aliza Nisenbaum, La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times, 2016. Collection of Jackson Tang, New York. Courtesy the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York. © Aliza Nisenbaum

Other artists offer glimpses of homes left behind. In Hayv Kahraman’s painting, “Bab el Sheikh” (2013), ghostly figures float above the floor plan of a traditional house in Baghdad, where the artist lived before her Kurdish family fled Iraq. The painting hangs near Do Ho Suh’s delicate fabric sculptures, which recreate rooms from his childhood home in Korea in translucent pink and gold polyester. You can walk through the life-size entryway and breakfast nook, each painstakingly detailed—down to the doorknobs, hinges, and wall sockets—yet as diaphanous as a dream or a memory. Aliza Nisenbaum’s painting “La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times” (2016) shows a father and daughter sharing sections of a newspaper in their new home in New York, but their former home in Puebla is present, too, in the vibrant talavera tile in the background.

Nisenbaum’s own family immigrated to Mexico before World War II, fleeing pogroms in Russia; she in turn came to the United States at age twenty-one and made her way to New York, where she taught a class called “English through Feminist Art History” that connected her with some of the undocumented immigrants who have become her portrait subjects. That kind of story would fit right in British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare’s “The American Library” (2018), a maximalist tribute to multiculturalism that fills the final room of the exhibit with six thousand books covered in colorful wax-printed cotton, a globetrotting textile originally inspired by Indonesian batik, produced by Dutch colonizers, and sold in West Africa. The books’ spines are embossed with the names of prominent Americans who are immigrants, the descendants of immigrants, or members of African American families uprooted during the Great Migration. Tablets in the center of the room allow visitors to look up the backstories of these boldfaced names—from Audre Lorde and Jessica Alba to Steve Jobs and Donald Trump—and add their own family’s migration history.

Yinka Shonibare CBE, The American Library, 2018. Installation view, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston. Photo by Mel Taing. © Yinka Shonibare CBE

Boston may be hundreds of miles from the tragedies unfolding along the southern border, but more than a quarter of its residents are immigrants, and our city is far from exempt from our country’s long history of mistreating migrants. The wall text accompanying the exhibition notes that the ICA’s new Watershed space is located in the Boston Harbor Shipyard that formerly housed the East Boston Immigration Station. Built a century ago to process immigrants, it was also used to detain Japanese, German, and Italian immigrants during World War II, a time when the US government turned away thousands of Jewish refugees. Today, with displacement due to violent conflict and persecution at record highs, this exhibition offers vivid reminders that policy questions regarding immigration and asylum remain moral ones, with life-and-death stakes, and that the political is always personal.

“When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art” is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston through January 26, 2020.