The winner of the deCordova Museum and Sculpture Park’s 2020 Rappaport Prize, Sonya Clark is a multimedia artist best known for her textile-based works exploring African American experiences and craft-based traditions, as well as challenging symbols of white supremacy. Clark has engaged with the Confederate battle flag in numerous ways, unraveling it thread by thread, or weaving its pattern into that of the American flag, to name a few. Her work Unraveling garnered attention in 2015, but as this hard-fought election year comes to a tumultuous close, I have found that its continued relevance is unfortunately obvious.

In the spring of 2021, the deCordova will host two exhibitions featuring Clark’s work. “Monumental Cloth, The Flag We Should Know,” organized by the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, highlights the historically significant yet little-known Confederate truce flag. As a fellow former Virginian, who grew up surrounded by the historic markers, place names, symbolism, and storytelling that continues the unhealthy work of keeping the South’s Confederate romance alive, I recognize with shock that I was wholly unaware that such a flag existed, let alone that a piece of it was preserved in the Smithsonian (where Clark herself first saw it displayed), prior to encountering Clark’s work. The second exhibition, “Heavenly Bound,” will comprise Clark’s recent work responding to the journey of formerly enslaved people on the Underground Railroad, including an installation invoking the Big Dipper and North Star, composed of the artist’s hair. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation from November 2020.

Olivia Kiers: Congratulations on receiving the 2020 Rappaport Prize! What did you think when you learned the news?

Sonya Clark: I’d been working with the deCordova on the shows “Monumental Cloth, The Flag We Should Know” and also “Heavenly Bound.” When the curators called me, I thought it was about business, maybe even one of those calls during this time of the pandemic saying we may need to cut back. Getting a prize, especially an unexpected one, feels like I have some guardian angels, like the ancestors are looking out for me. It’s good news—but when you get it, there’s responsibility. What are you going to do with that good news?

OK: And what are you going to do with that good news?

SC: I have a couple of projects in the works. These days, I’ve been intersecting with a crowd of artists and activists who are really interrogating the carceral state in the United States of America and visualizing what abolition would look like. I’ve had the opportunity to work with individuals who are incarcerated, who helped me make a project that I was working on even better than I had conceived of it, and taught me a lot about how I think of freedom. I hold in my mind this phrase from Toni Morrison: “The purpose of freedom is to free somebody else.” I’ve been thinking about how I might use the prize to again further my freedom to others.

Sonya Clark, in collaboration with The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia. Monumental Cloth, The Flag We Should Know, 2019. Installation view. Photo by Carlos Avendaño.

Sonya Clark, in collaboration with The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia. Woven replica of the Confederate Flag of Truce, 2019. Photo by Carlos Avendaño

OK: I listened to the Monument Lab podcast from 2019, when you were working on “Monumental Cloth.” Talking about the Confederate Flag of Truce, a piece of American history we have collectively forgotten over time, you said part of your role there was to amplify what is little known. What other roles do you see yourself fulfilling as an artist?

SC: You know, I think of artists as being thought producers. Art can shape and change thinking. It’s actually part of how we define ourselves. It’s really a powerful thing, a connective tissue.

I’m teaching a course now [at Amherst College] on beading. Beads are pretty, little, shiny things, but they were also used to pay for humans that were trafficked in slavery. They are signs of culture, and they are also—depending on what the beads are made of—about the environment. Some of the earliest productions of mankind are beads found on the continent of Africa. The point is, you can reach all of those things through a simple medium that has been trivialized because it is pretty, and gendered, also. It’s wonderful to be able to unpack all that in a liberal arts setting.

OK: A lot of your work is rooted in history and identity. Do you find yourself intentionally researching as you pursue new ideas for your work—or is your process more organic?

SC: That’s a both/and question. It’s not an either/or. Sometimes I will start with a medium—like the beads― asking, what else can we unpack here? That’s starting at the center, then having this radial complexity to understand something, right? To understand that the drop in the ocean in fact can connect to the whole ocean.

I feel like the heart of your questions is “Where does inspiration come from, and how does one follow it?” Sometimes it feels like serendipity. Like a gift. Like a Rappaport Prize. You gotta do something with that!

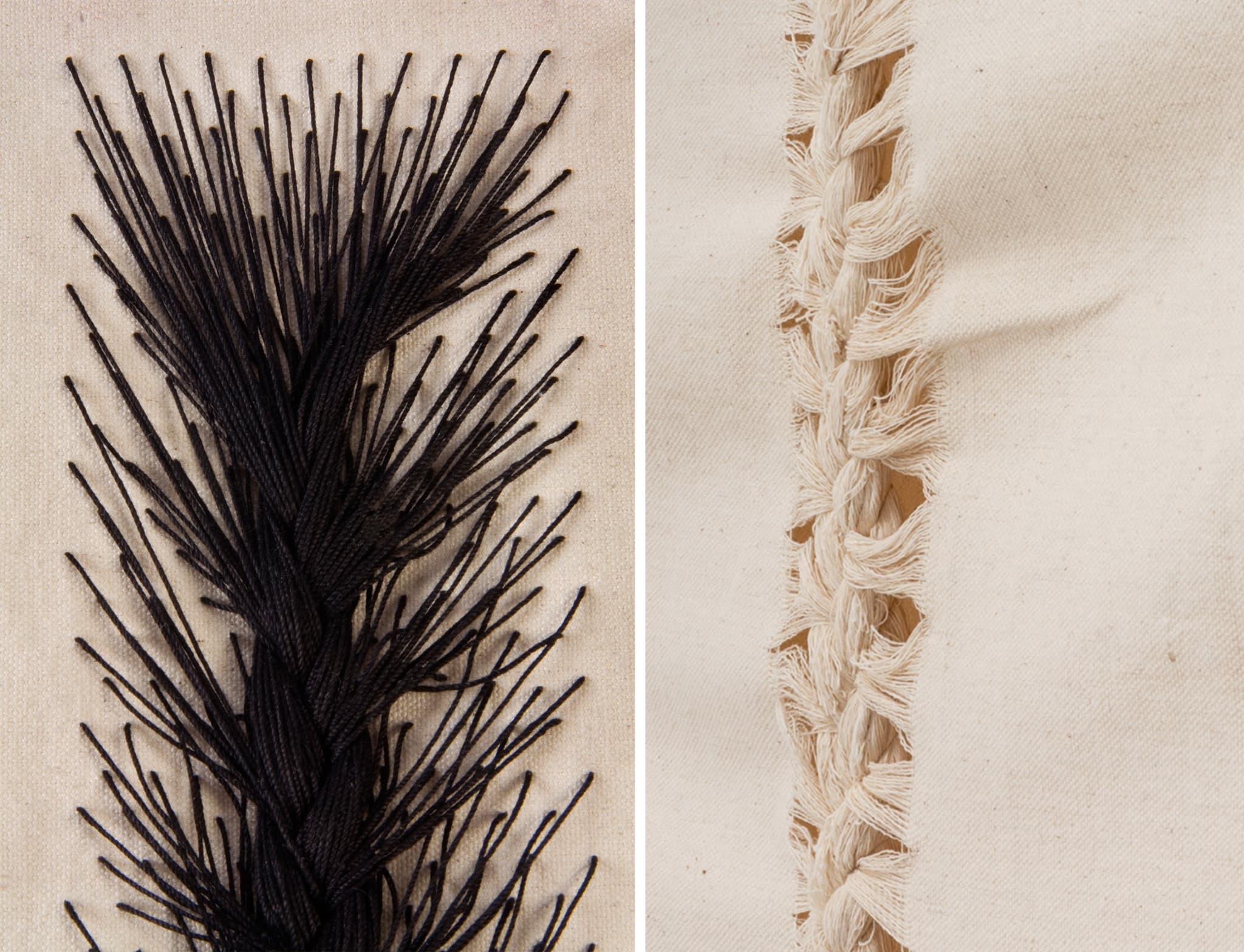

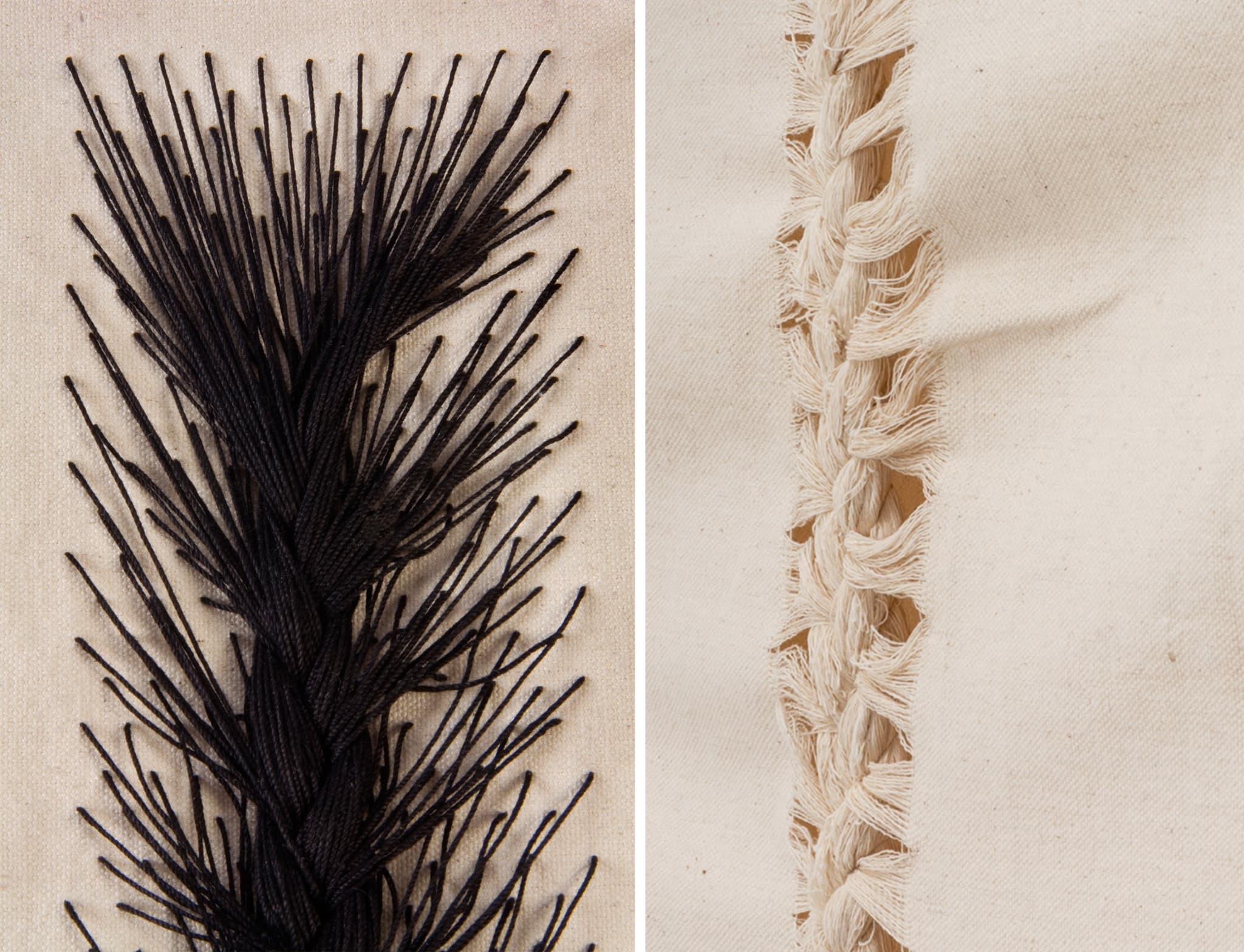

I had a student once who said to me, in trying to understand cornrows, “Well, a cornrow is really nothing but a small French braid.” This is a in order to understand, they’d reframe it in this way: nothing but a small French braid. I ended up making a piece called French Braid and Cornrow, engaging questions about cultures coming together, perhaps even cultural appropriation. It came from someone making an innocuous comment, understanding through a different lens. European American student. And I thought that was so interesting, that

French Braid and Cornrow, 2013. Detail view. Cloth, thread, wood. Photo by Taylor Dabney. Courtesy of the artist.

OK: Thinking about lenses, when you make a work of art, do you have a specific kind of audience in mind for each piece? Do you consider the race of the viewer during your creative process?

SC: Well, even if I were―so, I’m a Black person, but I can’t speak for all Black people. When I make an artwork, I might be asking a question, which means that the art has the capacity to be a mirror, to absorb all the answers. There might be works that are more didactic. But, even when you are telling something, the ways that something is heard can be really different. We are talking about context, right?

Some of my work intentionally engages audiences, and those audiences are quite broad in terms of race. For example, a piece like Unraveling [a work in which Clark invites participants to help her unravel a Confederate battle flag, first performed in 2015] is a didactic piece. It is about dismantling a symbol of white supremacy and white terrorism in this nation. But, because I never know who might stand next to me and what they might say, I have to always be ready to improvise. There was someone who was so triggered that her hands were shaking. That flag is a symbol of terror, so there’s no question why. To that person I said, “It’s just a piece of cloth.” Just to say, it’s just a structure that can be dismantled. But I also had someone come to me and say, “I have a relative who voted for Trump, and a relative who is a member of the KKK, so I am here because of that.” And to that person, I said, “You know, this is really only a metaphor. You have to go talk to your people.” To both people I am saying, “This is just a piece of cloth.” But for completely different reasons.

OK: When you are doing a piece like Unraveling, you are in the space with this very charged piece of cloth. As an artist, does it weigh on you?

SC: As a Black woman in America, white supremacy, white nationalism, white terrorism, and the injustices of this nation are injustices that need to be righted. They need to be undone. So any burden that I might feel from that feels more like responsibility. I’m actually in a pretty privileged place. People have lost their lives doing less than I have done and provided the space for me to be here. I lived in Richmond, Virginia, for twelve years. There were Confederate flags in lots of spaces there. So I was doing all sorts of pieces around it. When I was making [Unraveling], I used to have a lot of Confederate flags in my studio space, which at some point was like [Clark laughs and raises her hands in a stop gesture].

You know, a battle flag for a lost war shouldn’t ever be hung or flown. So then I thought, we need to focus on the truce, and on the complications of that truce as well. That probably is what led me in part to get to the Confederate truce flag. To make “Monumental Cloth.” To make something that people don’t know. And why do people know this battle flag to begin with? It wasn’t the only Confederate flag. Lots of people who love to dig into Civil War history will tell you, that’s not actually the Confederate flag. The reason we know it so well is because it was used by the KKK. It was used as a symbol of terror.

Unraveling (performance), 2015 – present. Confederate battle flag. Photo by Taylor Dabney

Unraveled, 2015. Completely unraveled cotton Confederate battle flag and shelf,10in x 3ft x 7in.

OK: The way symbolism can create visceral reactions leads me to my next question. I wanted to discuss embodiment in your work. I’m thinking about that in two ways. There is a sense of objects activating history in “Monumental Cloth.” But I’m also thinking of bodies in a more literal way, like The Hair Craft Project, or the many pieces you do that reference hands and hair. What does it mean to engage with the body?

SC: I got into studying textiles in particular because of the body. Textiles is a medium where people have a visceral understanding of it. It is a medium with a haptic quality. There’s this embodied knowledge. But there is also this way that knits or weaves—textiles that are with us all the time—have mystery to them, in terms of their construction. They are like our bodies. You may have an intimate awareness of it, but you don’t really understand how it works, unless you’re a physician.

Then, I’m steeped in craft-based traditions, a historical connection to those who have come before me, especially those of my African heritage who were valued more for the technologies they embodied: their ability to weave a basket, do ironwork, or make a vessel out of clay. That made you a more valuable commodity than your own humanity. So these technological skills were passed down through generations. Being in that legacy is important to me as well.

Pieces like The Hair Craft Project are about attending to embodied art practices, like hair braiding, that also follow that same kind of legacy from the continent of Africa to the Americas through the African diaspora. But like I mentioned before with beadwork, it’s a thing we take for granted, and it gets gendered. [Hair braiding] is complicated! And it comes from this rich tradition. So let’s frame that and focus on the complication of it.

The Hair Craft Project, 2014. C-print. Photos by Naoko Wowsugi. Collection of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Courtesy of the artist.

OK: My last question is, whose work are you looking at? Who is on your list of people to know?

SC: It’s probably too long a list to engage! Can you see what’s behind me? [Clark gestures to tall stacks of books. Some on top have the solidarity fist cut into the page ends.] They are actually books with the solidarity fist in them. So I’m doing this whole [Solidarity Book Project] because I love books so much. If you start asking me which books, it’s all of these books, and all of these books, and all of these… There are books or authors that I return to, again and again. I almost want to turn the question back on you and ask, is your intent in asking that question about endorsement, or is it about trying to understand where influence comes from?

OK: Both are interesting.

SC: Because if it’s endorsement, I have hundreds of books. There are the usual suspects: James Baldwin, Toni Morrison. I have a Paul Robeson quote on my wall that says, “The artist must elect to fight for freedom or for slavery. I have made my choice, because I had no alternative.” Text lives around me all the time.

I had the privilege of being taught by some amazing people like Nick Cave, who is a friend, and a former teacher. But the lessons that I have learned have come from everyone, from a small child who makes a simple observation to reading Zadie Smith or Imani Perry. I love literature. I love the way in which someone like Colson Whitehead can tell the truth of the history of this nation through fiction. There’s more truth-telling through fiction. That’s something I hope to embody myself in artwork. Truth through fiction.

Sonya Clark: Heavenly Bound, curated by Sam Adams and Sonya Clark: Monumental Cloth are on view at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum from April 10, 2021 – September 12, 2021.