Look at one of Ethan Murrow’s deckle-edged graphite drawings, and you’ll find precise details—the shine on the grommets of a shoe, the cinch on the wrist of a winter glove. In the background, an atmospheric weave of cross-hatched lines dissolves into soft focus, a quality that, from just a few feet away, could be mistaken for the work of a black-and-white film camera. The intricacy and photorealism of these often surreal scenes are the result of elaborate preparation. Before pencil touches paper, Ethan develops source material using research, props, costumes, photography, and performance. As the leading actor in most of his narrative illustrations, he often dons a suit coat or patterned blazer and a lush headdress of plants.

In Ethan’s Wareham Street studio—which includes an animator’s niche where his partner and collaborator Vita Murrow’s drafting table and video camera reside—I ask about his source material, and he points to a line of metal shelves filled with plastic bins. It is somewhat shocking to discover his “costume closet” and set of props are mostly thrift store finds, Scotch-taped masks, faux foliage, and computer printouts of slightly pixelated stock photos. What’s seen in real life or captured by the lens is transmuted by hand into gorgeously rendered works on paper, oil-painted canvases, wall drawings, and children’s book illustrations.

Ethan was my graduate school advisor at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. I recently reconnected with him while he was putting finishing touches on work for his solo show in New York City, making final plans for a mural project in Burlington, MA, and drafting pages for a graphic novel that will be published by Candlewick Press. With looming deadlines, I expected his studio to be in a frenzied state. Instead, it was a space of calm focus. During our meeting, he spoke about his current research, the joy of being alive, and his love for his partner, family, colleagues, and team.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed.

Ethan Murrow, Thin Ice, 2023. Graphite on paper. 48 x 36 inches. Photo by Julia Featheringill Photography.

Monica Lynn Manoski: You were born in Massachusetts and grew up on a sheep farm in Vermont. Can you share a bit about your childhood and how growing up in that environment shapes your work today?

Ethan Murrow: That’s true, and it’s important to qualify. It was a hobby farm—a progressive-liberals-move-to-the-country experiment with a lot of hijinks involved. My parents were from the city and moved to rural Vermont during the Vietnam War. They were novices trying something new. We were always learning, and we had lots of failures. My parents were honest that they didn’t totally know what they were doing, and we weren’t making any money doing it. They had jobs as teachers. The playful experimentation we were lucky to engage in on the farm was a big part of my childhood, and it made me more comfortable with risk in the creative field. Raising animals or crops is a constant reminder of how fragile our relationship is with the rest of the world, and that shows up in my work. In the biggest way, it gave me a love of the land and animals and helped me see that we humans are guests here and lucky to live on this planet.

MLM: You and your partner, Vita Murrow, are individually and collectively creative forces. As an animator and writer, she brings a unique perspective to your collaborations. You’ve created two picture books together, and you’re currently working on an eighty-page graphic novel. Can you share your experience working on projects with your wife?

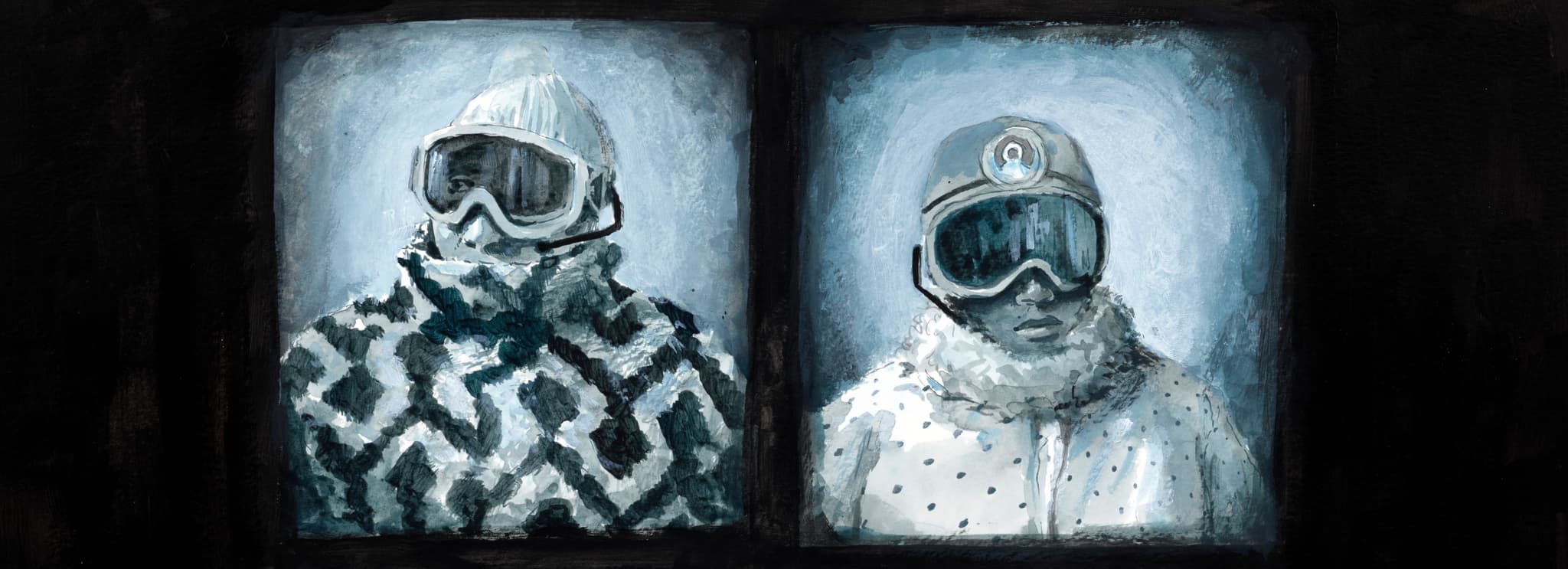

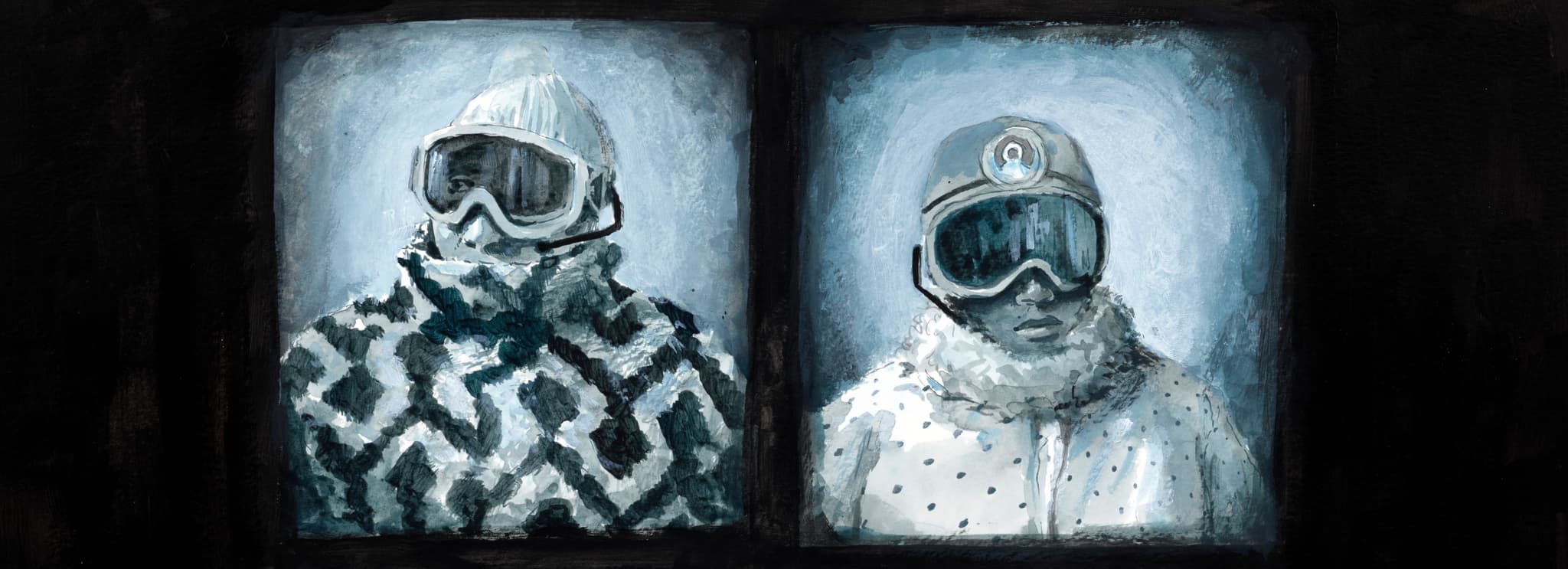

Sample artwork for a graphic novel made with Vita Murrow and forthcoming from Candlewick Press. Photo by Julia Featheringill Photography.

EM: Working with Vita is a joy. We’ve come to a new place in our relationship because of working together. We’ve had to clarify what it means to be both a critic and supporter of each other’s work. I read a lot of her writing; she reviews a lot of my drawings and paintings and gives great feedback. Then we have our family life. Learning how to build boundaries and clarifying what’s most important means that we need to be laser-focused when we work together. Vita and I got our creative start making short films together. Those projects were vital as we transitioned into the book world. We realized the structured approach to conceiving a film, where you think about the narrative arc, was helpful for children’s literature. We often build elaborate sets and props and work with actors and photographers to develop source material. Then we transition into drawings and paintings, which are the content of the book. Many artists working in this genre have much simpler processes, but our steps give us time to talk and refine the narrative. The slowness sometimes frustrates us and those we work with, but we hope it enriches the imagery and story. Even though it can be difficult, we feel lucky to work together. We both have jobs we love, and you can’t ask for much more than that.

MLM: You’ve spoken about the importance of being a father and how that role informs everything you do as an artist. Can you share how being a parent influences your practice?

EM: Becoming a parent clarified things for me in a really wonderful way. My kids, my partner, and our home life have always been the most important thing. Being an artist is an incredible job, and I feel lucky to have it, but it comes second to loving and living with the people in my life. When we had our first kiddo, I knew exactly what I had to do in the studio, not in terms of my content or concept, but in terms of my habits. It meant when I came into the studio, I had to get stuff done, and I had to do it clearly and concisely because I wanted to be home as much as possible.

MLM: Your upcoming show at Winston Wächter in New York opens on September 5. It will include twenty-two new works that illustrate the magic and mystery of trees and how we use and misuse the forest’s resources. I’d love for you to tell the story of The Nursery.

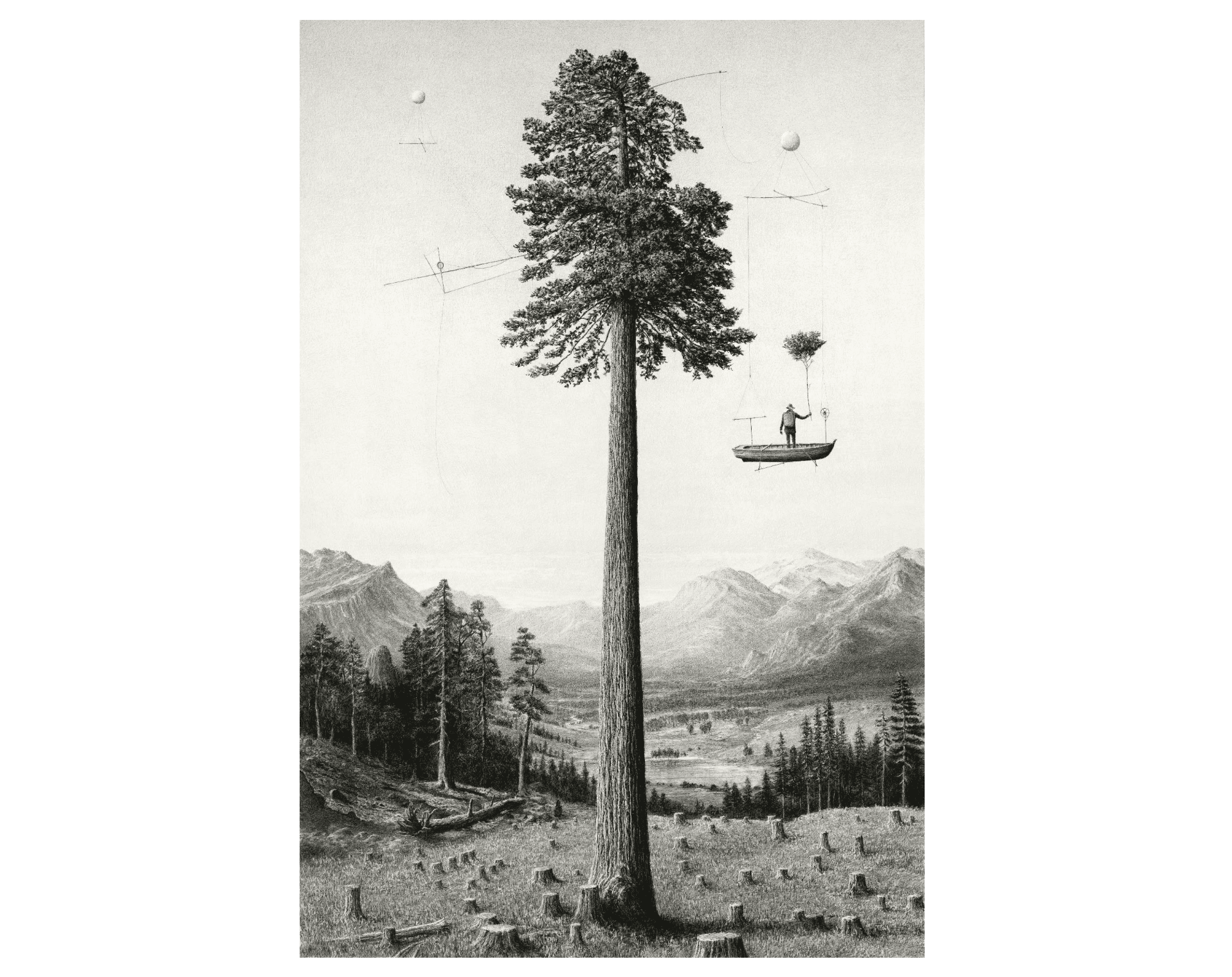

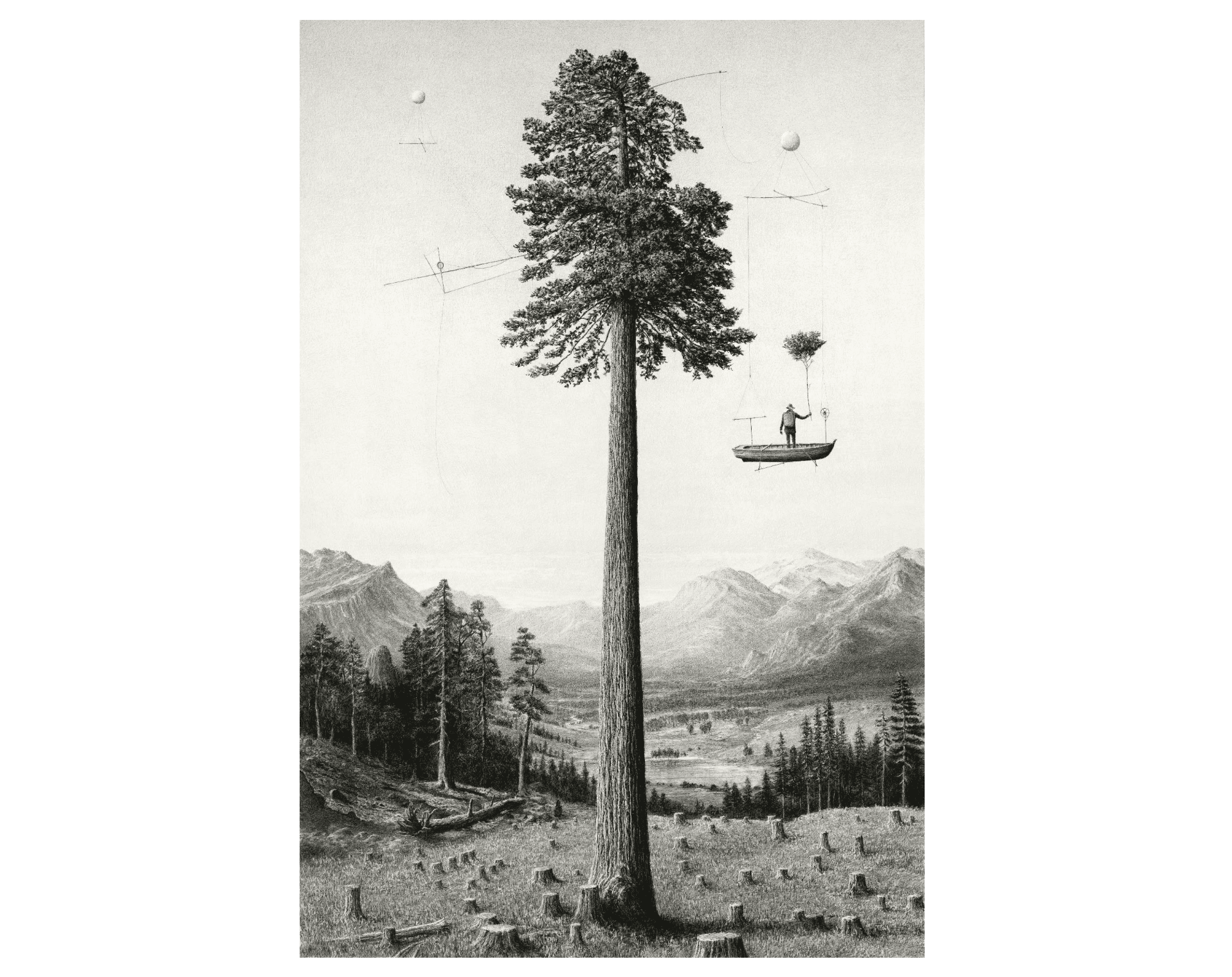

Ethan Murrow, The Nursery, 2024. Graphite on paper. 72 x 48 inches. Photo by Julia Featheringill Photography.

EM: This 72-by-48-inch graphite drawing depicts a fully fledged old-growth tree in British Columbia. Surrounding it are references from historical landscape painting, imagery from photography I’ve taken, plus plenty of invented components. The focal point is a massive tree surrounded by cut woodland, and there’s a character in a boat, suspended from the tree. There are questions about purpose and intent: maybe this person is the forester or the arborist, perhaps they’re helping the tree, or maybe they’re the one that will cut it down. I try to set up narrative cliffs where we don’t know what the character’s purpose might be, and I’m hoping that builds tension in the work. We humans, out of naivete or ignorance, often corrupt things, but we’re also capable of being wonderful, thoughtful, protective, and collaborative. I don’t always know what these characters will do, but I love fiction, I love stories, and I love finding ways to build an environment where viewers might craft their own tales from what I’ve started.

MLM: Working in self-portraiture, one of the things you grapple with as the protagonist is your role as a lone white male figure in the landscape. You tend to use humor and poke fun at yourself and our human inability to solve so many of the conundrums we find ourselves in. Can you speak to the playful nature of your work?

EM: My self-portraiture sets up scenarios where I’m always implicated. Some characters have a heroic quality, but I undercut their potential for success, laying fragile groundwork, suggesting that their boat might sink; the person may never have asked anyone else if what they were doing was a good idea, whether they should even be there in the first place. I’m hoping that by being the protagonists in the space where those questions exist, I’ll encourage viewers to grapple with these issues, too. So much of my work focuses on landscape, how we use it, abuse it, love it, fear it, and find solace in it. A big part of that concerns ownership and who has a say. I don’t have the answers, but I know my role as a white male artist making this work is pretty fraught, and it would be remiss of me not to talk about it. For me, it is a lifelong project; no individual drawing can answer these questions.

I try to come from a space of joy, that total absurd sense of possibility that you feel in the right circumstances: in a rainstorm, on top of the mountain. In my opinion, that’s a good starting place for finding some common ground. Breathing in the raw landscape allows us to think about who we are as individuals and who we are together. I hope the work illustrates that these characters love what they’re doing. They love being out in the world. They love plants, they love getting dirty, they love getting wet. While it can feel like it almost leaves out these big questions, I hope it provides a beginning point for getting into the messiness, which is really important to think about and discuss.

MLM: Yes, life’s work for sure. And love is the glue that holds everything together, so I think it’s a perfect place to start.

Performance is a key facet of your practice, and working with dancers, actors, and photographers is another aspect of the collaborative nature of your work. You expressed the exuberant joy you feel while performing for the camera. Can you speak to the embodied nature of your practice?

Ethan Murrow during a photo shoot on Plum Island. Photo by Julia Featheringill Photography.

EM: I started thinking about performance when collaborating on film projects with Vita. She was trained as a videographer and photographer, so she was behind the camera, and I performed more often. I love thinking about the physicality of the human form and how we can suggest emotion and intent through gesture and motion. I wear costumes for my work, and being covered, I feel so much more capable of letting my body try things: twists, turns, jumps, and stumbles. Danielle Abrams, who sadly passed away, was a longtime friend and colleague at SMFA who helped me say out loud that I was a performance artist. It’s so funny, these simple things people say. It probably moved through her mind quickly, but it was so important to me to affirm that as a component of my practice.

MLM: In August, you will begin work on a 27′ x 9′ mural for the Broad Institute Clinical Labs in Burlington, MA. You’ve expressed how so much of your work could not happen without the help of your studio assistants. Can you talk about the team you work with and how the collaborative nature of your work influences the finished piece?

EM: As I started working on murals, many of which are months-long, multistory projects, I realized I had to have more help. I’m lucky to know a lot of amazingly skilled emerging artists, particularly through teaching at SMFA. Nicolas Papa works as my studio manager and does everything under the sun, from running the business to building the first stages of drawings and ensuring the logistics of each show. I learn so much from everyone I work with, and the work is always better when other people are involved. The murals have been a place to celebrate and learn from my collaborators. Having other people fill the gaps when you lose energy and bring skills you don’t have is priceless. The murals are always exciting; the time constrictions force you to troubleshoot. Luckily, I know the others I’m working with will help me solve it. The collective is important, and when we’re done, there’s a party atmosphere that feels so good.

Ethan Murrow, detail of a mockup for a forthcoming mural for Broad Institute Clinical Labs, Burlington, MA.