Direct experience of psychic phenomena is often viewed as proof that God, Spirit, or some divine source not only exists, but is within reach. There are times in human history when awareness of the other side becomes more prevalent. When this veil thins, spirit manifestations and interests therein increase. Ever since the planet of transcendent spiritual experience, Neptune, entered Pisces in April 2011, astrologers have observed that we’ve been living through one of those heightened periods. From 1847 to 1861, the last time Neptune transited Pisces, the sensitizing energy gave rise to the Spiritualist movement and a potent period of Shaker history called the Era of Manifestations.1 The development of these movements was centered particularly in Massachusetts and a part of New York called the “Burned-Over District.” With the twenty-first-century explosion in popularity of the occult, including divination, witchcraft, mediumship, channeled artmaking, and goddess and ancestor worship, the past has felt exceedingly present. Similar to the mid-1800s with the rise of first-wave feminism alongside abolitionism, the practice of spirit communication has coincided with major decolonial, feminist, and anti-racist social justice movements in America, such as Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, Land Back, Me Too, and Free Palestine.

While we’re once again experiencing a collision of esoteric and social justice movements, there has not been much improvement in how mainstream media and institutions depict direct experiences of Spirit since the nineteenth century. Oversimplified stories that focus on shock value for revenue ignore how belief systems rooted in earnest spiritual attunement help to construct alternate worlds, create real change, and engage socio-spiritual experimentation as common practice. Over the last decade, there has been a proliferation of visual artists working openly with channeled and psychic processes, some even drawing inspiration from Shaker and Spiritualist disciplines. Yet the art world itself has not always had the best tools to contextualize such creative reawakening or to support the living mystic laborers it benefits from. We aim to highlight some of the hidden yet crucial perspectives that can help the contemporary appreciator of mystical art, labor, and culture better understand what they are consuming and even reliving.

And who will tell this version of the story? Maria Molteni is an interdisciplinary artist, Shaker researcher, and member of an active Spiritualist community in Massachusetts’s Pioneer Valley. Known as Lake Pleasant, this community dates back to the earliest days of Spiritualism, as does New York’s Lily Dale, which is the most active Spiritualist community today. Last summer, Molteni hosted an eight-day socially engaged art pilgrimage called “Great Awakenings” with collaborator Melissa Nierman of NowAge Travel. It carried five queer mystics from Salem to Lily Dale through sites that are important to Shaker, Spiritualist, abolitionist, queer, and feminist histories, particularly in the historical window referred to as the Second and Third Great Awakenings. Laura Campagna is an astrologer, energy healer, and writer who attended the radical road trip. The themes they studied together—through Molteni’s syllabus as well as the vibrant lectures witnessed at their adventure’s final stop, contemporary spirit photographer Shannon Taggart’s annual Lily Dale Symposium—have been further amplified this summer and fall by several art world shows. These exhibitions are unique in how they feature the work, scholarship, and documentation of both living and dead mystics in space and conversation with one another.

The niche overlap of Shaker and Spiritualist histories during periods of American history called Great Awakenings2 is rarely discussed, but there are nuanced similarities and even some encounters between channelers of both faiths. And while their overall histories, beliefs, and practices were quite different, they both grew out of the Quaker community and formed under strong female leadership seen as practically heretical for its time. Each movement developed quickly, peaked, and then dissipated. However, interest in their practices has grown immensely, and their legacies are still in process today.

The Shakers are often referred to as “America’s longest lasting Utopia”, a term they would not use to describe themselves. Instead of seeking “No Place” they tasked themselves with mirroring “Heaven on Earth” upon arrival from Manchester, England in 1774. The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing were nicknamed “Shaking Quakers” because of their mid-meeting eruptions of “ecstatic” dance. Their foundational beliefs in pacifism, gender, racial, and, class equality, communal ownership, channeled worship styles, a Mother-Father God, and sexual abstinence did not leave them well received in their new home of the forging United States.

Instead, the Shakers were viewed as heretical, radical, perverted, even “witches,” and contrary to declarations that the young Christian-nationalist, capitalist country was writing into law. Still, the Shakers’ matriarch, Mother Ann Lee, who was thought to be the Second Coming of Christ in female form, became an influential woman leader, though she died just ten years after arriving in New York, weakened by harsh beatings and prolonged imprisonment. Inspired by her magnetism, which was felt in her life and after her death, cloistered Shaker villages proliferated throughout the Eastern United States. Here they built egalitarian, labor-intensive communities safely separate from “The World” (how Shakers refer to life outside of their villages). At their height, there were eighteen Shaker Villages with hundreds of believers in each. Last year, 2024, marked the 250th anniversary of their arrival, celebrated by the two living Shakers, Brother Arnold and Sister June, who persist in Sabbathday Lake, Maine.

The Spiritualists were less tightly organized as a faith and congregation. Having started as a phenomenon, Spiritualism grew into a movement, an industry, a “science,” and eventually into a religion or spiritual philosophy. Spiritualism (as well as its Caribbean cousin Espiritismo) is defined by belief in communication with the dead and practices of public and private mediumship.

F. Adler, Investigate!: Do the Dead Return?, Broadside, Boston, circa 1881. Image courtesy of Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

Spiritualists believe that the ability to commune with spirits of the departed provides evidence of divine presence. They may attest to belief in God or in “Infinite Intelligence,” but all agree that death itself is not an end. Rather, it is a doorway to the afterlife, often called Summerland, where spirits continue to converse with the living. Direct communication with the divine was a central part of both Spiritualism and Shakerism, as were tenets of justice and equality. But while Shakers experimented with social models within self-sufficient, almost monastic societies, Spiritualists had a larger impact on both popular culture and socio-political affairs in the United States.

Countless faiths before and since Spiritualism have enshrined methods for intercession with the dead. The dominant story of Spiritualism in America tends to start in 1848, when teenage sisters Maggie and Kate Fox experienced a series of hauntings and percussive spirit “rappings” in their home in Hydesville, New York. While Spiritualism does not simply begin or end with the Fox sisters, their highly publicized experiences kicked off a frenzy of specialized interest in spirit communication and seance. In the mid-1800s, chattel slavery was nearing its peak, women were not allowed to speak in public, people died en masse from diseases, and nearly a million died in the Civil War. The need for a belief in something that could inspire the construction of a better world was evident. The empowerment of common people to cultivate their mediumship abilities posed a direct threat to the church’s authority. Feminine beings were considered ideal channels, and while this reinforced traditional stereotypes of women, it also opened up political platforms and employment avenues previously barred. Women seized this opportunity to not just deliver personal missives from the dead, but also to advocate for the abolition of slavery and the rights of women, including the ability to vote, get divorced, and practice temperance.

The original Spiritualists were largely, and openly, suffragists and abolitionists who broke off from more conservative Quaker congregations. Although there was no core text, the guiding principles were radical and contributed to the emerging feminist movement. Spiritualists rejected the biblical concept of original sin, thus absolving Eve of wrongdoing, and asserting that death was not the end of life. The Fox sisters also had connections to Quaker abolitionists in Rochester, notably Amy and Isaac Post, whose home was a stop on the Underground Railroad. The Posts collaborated with abolitionist author and Underground Railroad conductor Frederick Douglass, who lived in Rochester from 1847 to 1872. Sojourner Truth was famously active in Spiritualist communities, as was Boston abolitionist William Cooper Nell, who grew up in the free Black community of Beacon Hill and moved to Rochester to work with Douglass on his newspaper, The North Star.3 In 1872, Douglass was invited to become the running mate of the first woman to run for president in the United States, a Spiritualist, psychic medium, and medical intuitive named Victoria Claflin Woodhull who ran on the Equal Rights Party platform, advocating for abolition and free love.

The advances in legal rights and access to public office that women and anti-racist abolitionists won during this time cannot be uncoupled from the vehicle of Spiritualism and the public trance lectures that flooded theaters and lecture halls throughout New England and across the US. The numbers vary on how many people identified as Spiritualists, from hundreds of thousands to millions,4 but what is known is that there were hundreds of mediums in every US state by 1851,5 most of them women.

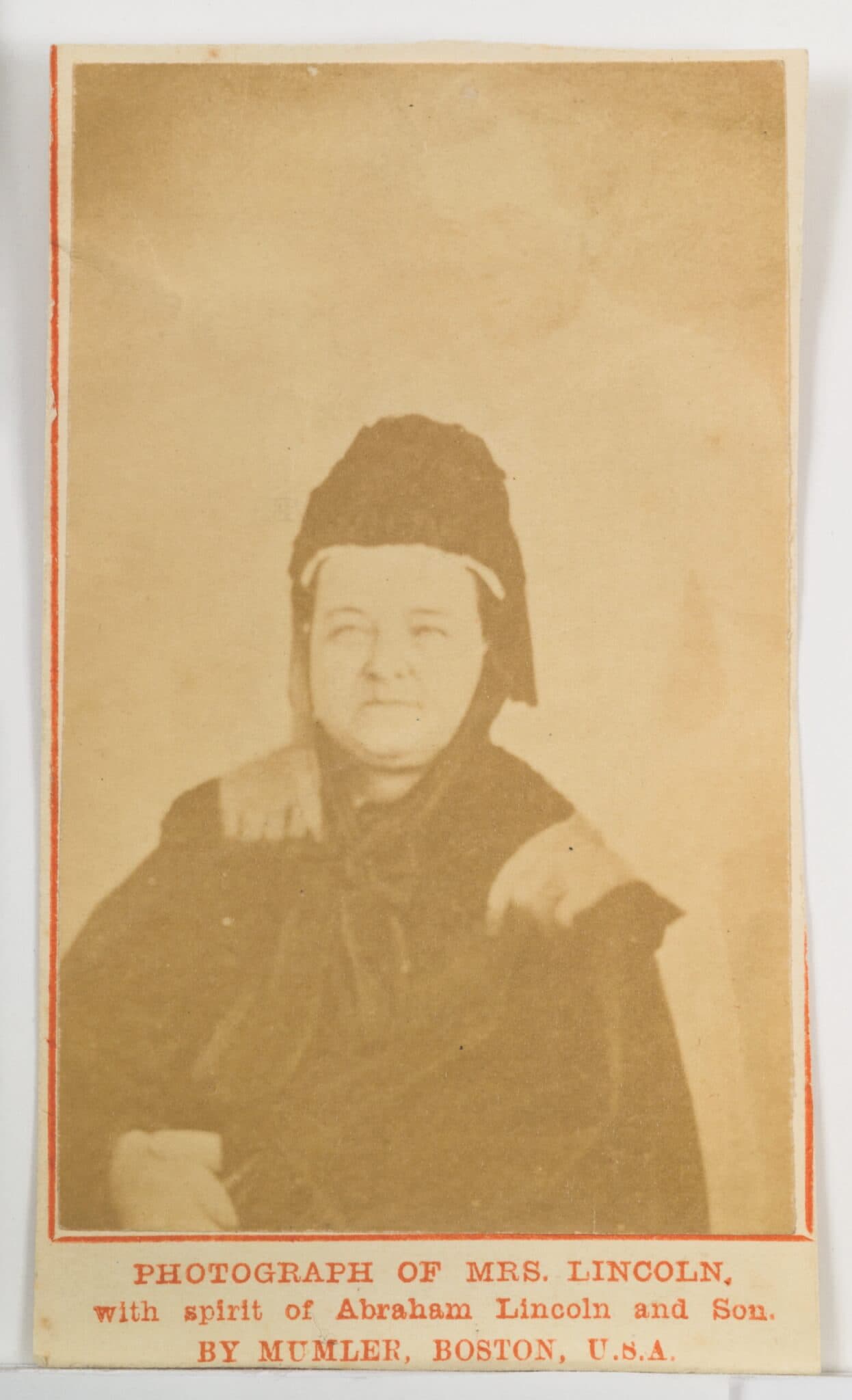

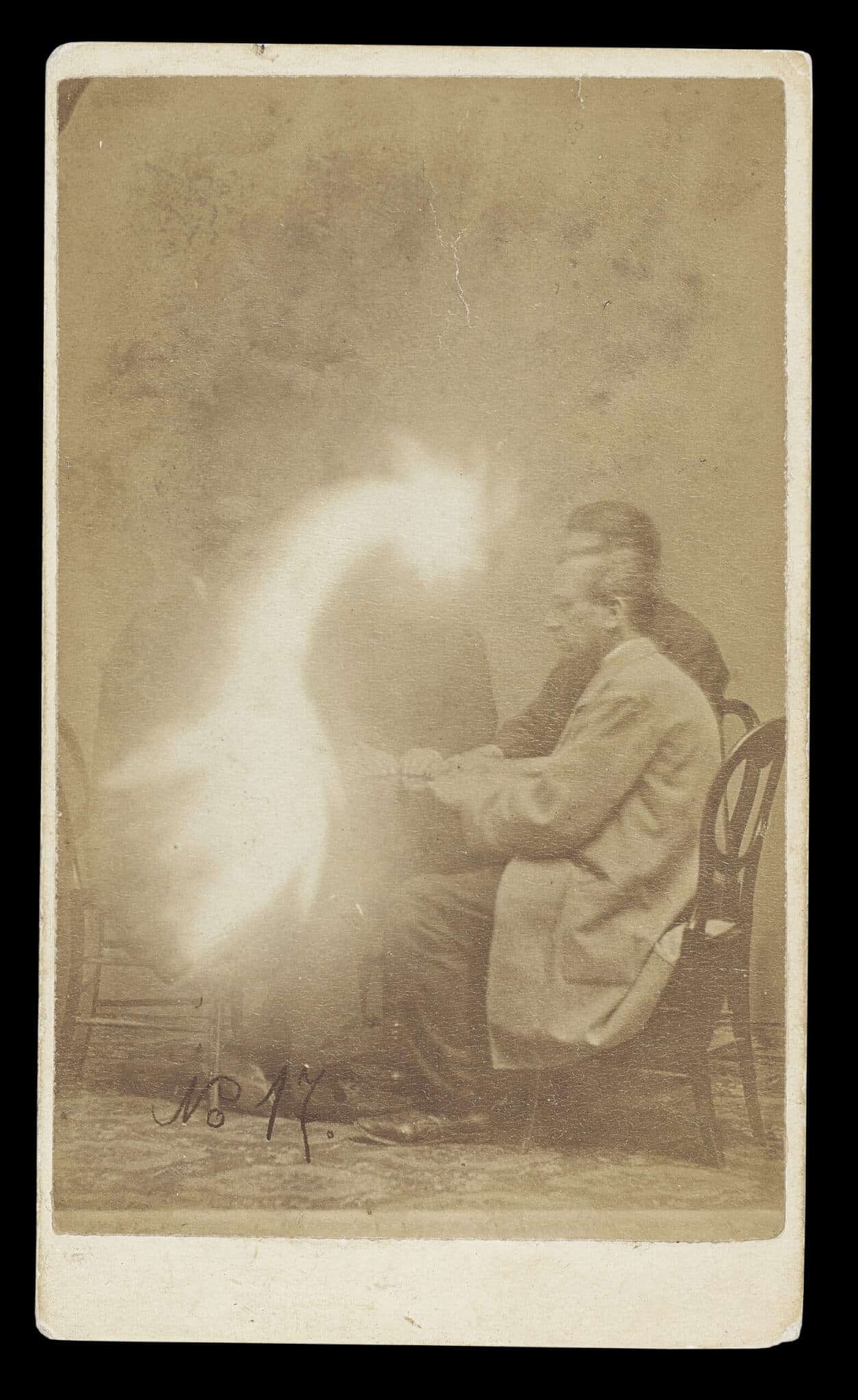

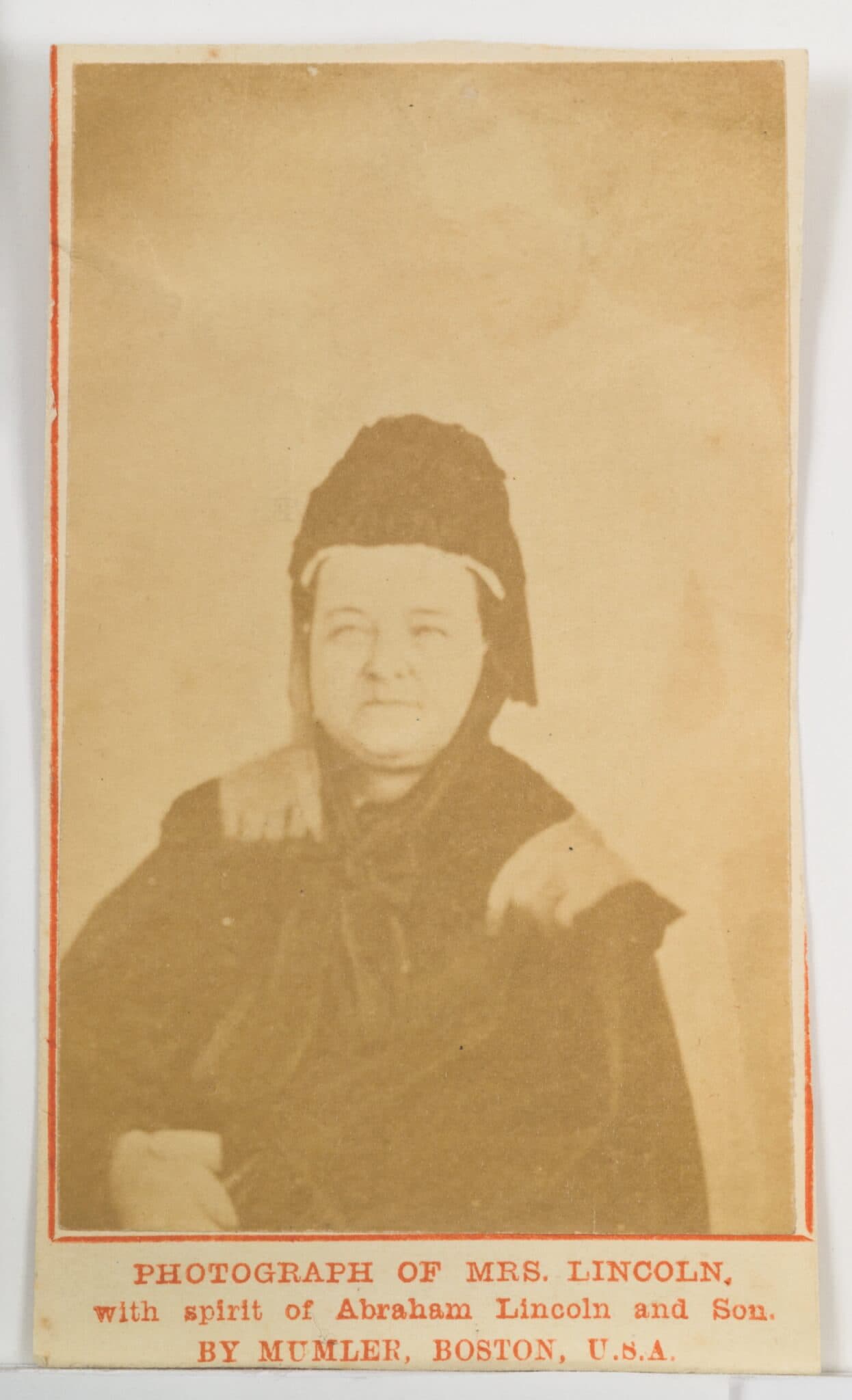

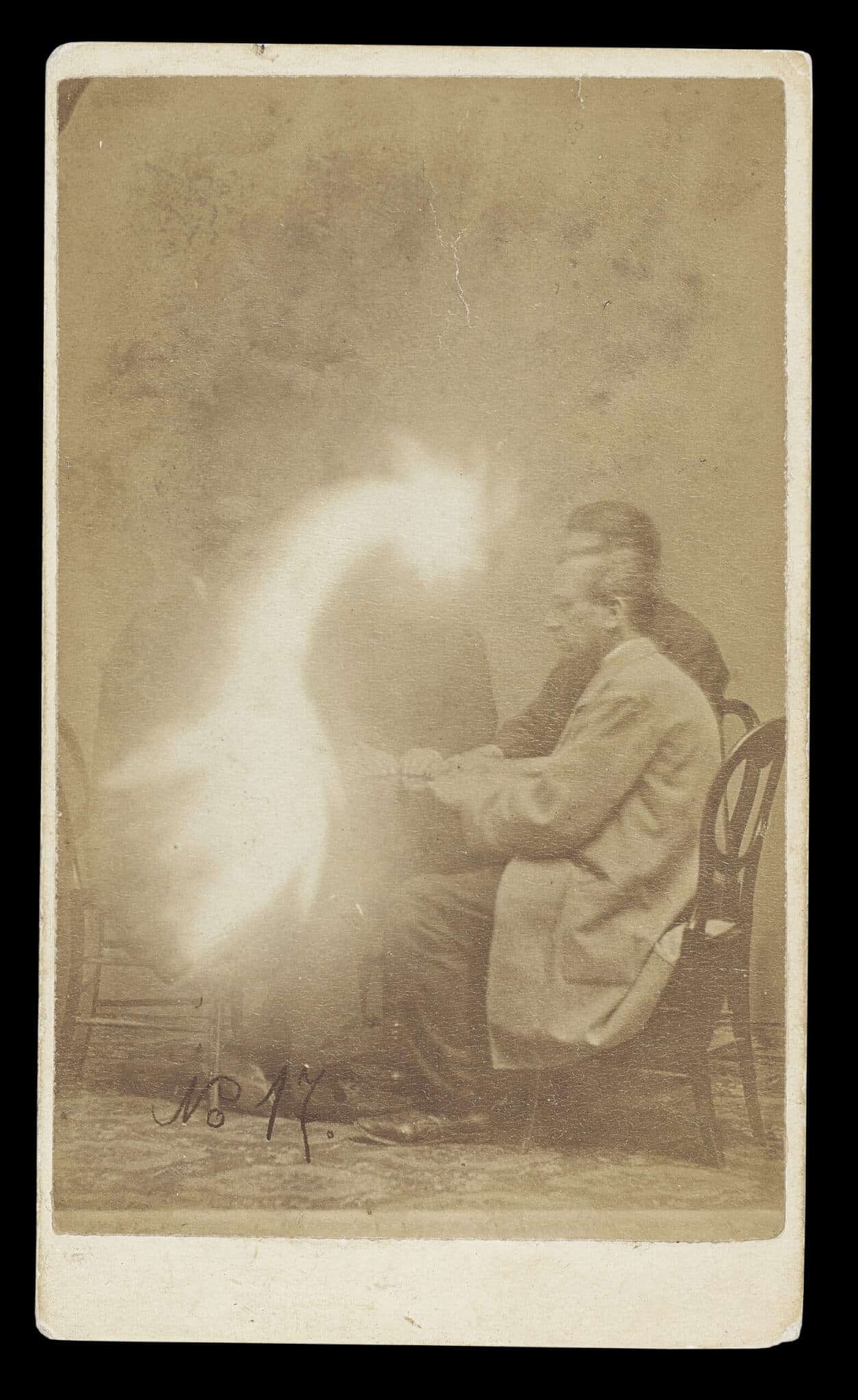

Meanwhile, in more private spaces, mediums served bereaved clients searching for connection, consolation, and answers from deceased loved ones. In more social spaces, seance attendees reveled in the glamor of psychic abilities. Some mediums toured the country hosting elaborate performative seances, which incorporated object mediumship, including spirit trumpets or ectoplasm, a glowing white substance that would emerge from the ears, mouth, neck, or even groin of the medium. The ectoplasmic seance created space for erotica that newly trained photographers tried to capture, whether for science, journalism, or art. William H. Mumler, the famous founder of spirit photography, worked out of Boston’s North End, where he invited clients to sit for portraits with guest ghost appearances.

William H. Mumler, Photograph of Mrs. Lincoln with spirit of Abraham Lincoln and Son, 1872. Albumen print. Collection of Tony Oursler. Photo courtesy of Oursler Studio and Peabody Essex Museum.

John Beattie, Abstract Manifestations, 1872. Albumen print. Collection of Tony Oursler. Photo courtesy of Oursler Studio and Peabody Essex Museum.

Whether Spiritualism was viewed as a religion, political movement, or industry, women were at the center of it all, as both stars and subjects. They were often critiqued and controlled by men, whether they were managers profiting off of psychic labor or spirit investigators seeking to discredit mediumship. From scientists and professors to magicians like Harry Houdini, men leveraged their power to debunk influential touring Spiritualists as fraudulent, not hesitating to perform invasive searches of women’s clothing and bodily cavities for their own proof. Some reported publicly that they could find no trace of fraud, but many succeeded in smear campaigns, with wide-reaching press coverage. This impact is evidenced by social perceptions of mediumship today.

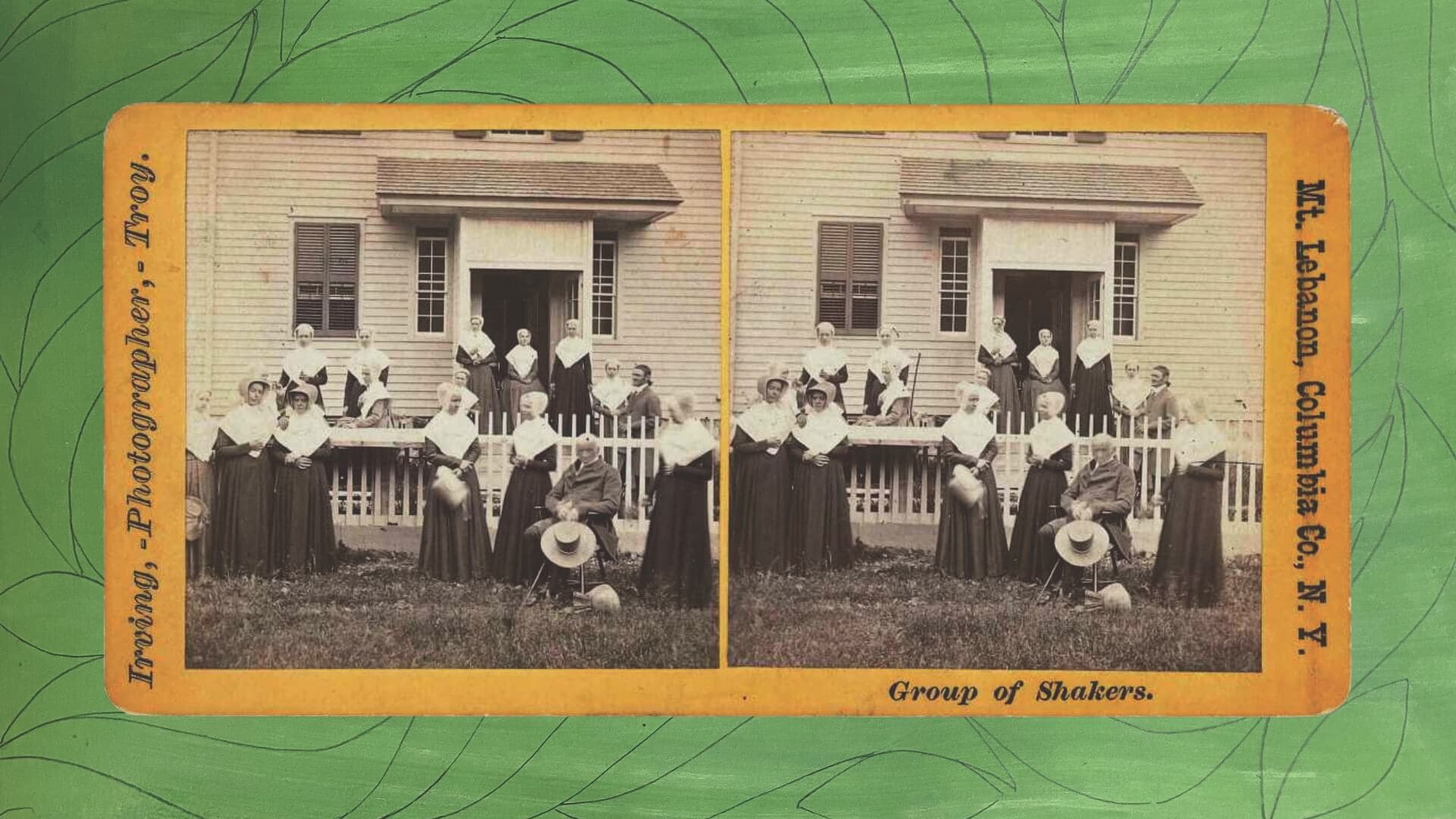

Parallels could be drawn between the impacts of Shaker and Spiritualist spectacle in public view. The Shakers held open Meetings, complete with structured and spirited dancing patterns, allowing visitors from “The World” to observe. This practice continues even today, as Molteni’s very first encounter with Shaker culture was attending an open service in Sabbathday Lake in 2007. This became an indirect tool for Shaker recruitment, but never for purposes of entertainment or “proving” their beliefs. Services were not performances, but they were often reviewed by press or travelogues in ways that could either help or harm the Shakers’ reputation. Published last fall, the New York Times article “There Are Only Two Shakers Left. They’ve Still Got Utopia in Their Sights” is a rare contemporary feature. Molteni is aware that Brother Arnold turned down interviews for such features for years prior. The headline quickly illustrates how word choice can greatly change present and historic perceptions.

The Shakers and Spiritualists both employed objects in spiritual contexts, but their explorations of visual and material output are inherently different. The ability to calibrate the ideal with the practical, to reflect divine assignment on the material plane, has been a unique strength of the Shakers. Central to Shaker daily life was the belief that labor is a form of worship, expressed by the often sung adage “Hands to Work, Hearts to God.” The famously crafted Shaker objects, from chairs to buildings, are inherently imbued with their metaphysical ideology. But the visual culture Shakers produced, including village map drawings and later documentary photography, was never divorced from utilitarian function. In fact, their Millennial Laws, a text setting standards for Shaker conduct, rejected the incorporation of “art” into their spaces or work schedules.

Still the Shaker method fosters the capacity to exist on multiple celestial planes while remaining present, and exceptionally productive, on earth. The Shakers so refined the binary that limiting dualities collapse into themselves. From architecture to dancing patterns, their symmetrical design reinforces mirrored relationships between here and there, male and female, self and community, heaven and earth, labor and worship, mundane and divine, life and death. Each dichotomy sits, not so much separated as co-confronting, locking eyes with a vast, unifying Divine. This transcendence was never made more vibrantly apparent through explicit records and depictions than during the Era of Manifestations (EOM), from roughly 1837 to 1857. This period was also called “Mother’s Work” due to the unprecedented nature of revelations delivered to the Shakers by their late leader, Mother Ann Lee. The EOM, as unique within Shaker history as the Shakers are within American history, punctuates an under emphasized cornerstone of their spirituality: communication with the other side.

Miranda Barber, Holy Mother Wisdom… To Eldress Dana or Mother, 1848. Ink and watercolor. Approximately 10 x 8 inches. Courtesy of Hancock Shaker Village.

While it was not uncommon to receive messages or dream-time visitations from the great Shaker Matriarch throughout their history, a seismic, perhaps cosmic energetic shift in Shakerland thinned the veil and opened the floodgates to a new era. The first events of the EOM were recorded at the first official Shaker Village, called Watervliet, in Niskayuna, New York, where Lee’s gravestone currently rests. In the winter of 1837, fourteen-year-old Ann Mariah Goff fell into a trance in the middle of her workday, experiencing one of many visions in which she toured the City of Paradise, meeting with Mother Ann Lee, Jesus, and other deceased Shaker ancestors. A transcription by Shaker Brother Isaac Newton Youngs reads:

At 1/2 past 7 in the morning there came a sister spirit to me, by name of Caroline Landon, and asked me to go with her. I went with her […] and we came to the city of Paradise. […] Then we went to a house, and there I saw a room which my guide told me was the first place Mother Ann came to after she left earth. […] There were rows of flowers of a golden color all around the room; and between the rows of flowers Mother Ann’s name was written, in large gold letters, all around the room, and at the beginning and end of her name was a large golden flower. I then started for home after an absence of seven hours and a half.

Soon many Shakers had similar visions, including physically consuming trance activity that interrupted daily life, as reports of sudden total loss of bodily control increased. Some of these “visionists” recounted their own experiences, but in many cases a Shaker “instrument” would record the experience of another. They began with written manuscripts, which could take the shape of leaves or hearts, eventually blooming into fully pictorial scenes now widely referred to as Gift Drawings.

Gift Drawing styles varied, but common motifs included hyper-sensory depictions of gardens and trees, the most iconic being Shaker sister Hannah Cohoon’s Tree of Life (1854) and Tree of Light (1845), frequently flanked by text-based transcriptions. Others depicted luscious scenes of heavenly cities, celestial mansions, and luxurious gifts available to Shakers in a Paradise not entirely separated from village grounds. Delicately drawn shining lanterns, circles of jewels, baskets of fruit, and sweet-sounding trumpets and birds could also be found. Imagery might mimic Masonic symbolism, like all-seeing eyes, one of which inspired the CBS logo. Some messages—such as A Present from Mother Lucy to Eliza Ann Taylor (1849) by sister Polly Jane Reed—were addressed as gifts to specific living Shakers and labeled as such. These drawings came to prove that Mother’s Work was not just a thing of the past, nor solely shrouded in trauma. Mother Ann continued to bestow blessings, praises, and love in the form of glistening treasures upon her children from the afterlife.

Hannah Cohoon, The Tree of Light or Blazing Tree, 1845. Ink and watercolor. Approximately 18 x 22 inches. Courtesy of Hancock Shaker Village.

The dawn of the EOM predated the commonly accepted birth of Spiritualism by a decade, but there was concurrent Spirit activity through the 1850s. As the popularity of Spiritualism grew through circles associated with high-society celebrity, Shakers also made contact with prophets and famous figures. These might include deceased presidents, even historic villains like Christopher Columbus, who came through repenting his earthly atrocities. Rare writings by Shaker polymath Henry Blinn include conversations with the spirits of Black and Indigenous figures who were ready to weigh in on the judgment of such sinners. In his summary of the EOM, Blinn also adopts some Spiritualist phrasing, referring to “mediumship” among the Shakers and even “Summerland” as the place where the dead pass on to. On rare occasions, some Shakers even ventured out of the village to attend Spiritualist seances, and vice versa. Initially, Shakers believed that Spiritualism’s explosion on the scene was proof of their own influence on “The World.”

There were notable differences in how Shaker and Spiritualist channelers were received. Many Spiritualists attained significant fame for a time, but were overworked, exploited, or violated by intrusive doctors. Conversely, Shakers were taken seriously enough for their visions to become woven into the fabric of daily labor and worship practices, as Mount Lebanon’s Central Ministry implemented protocol for reviewing and vetting channeled documents. But as neighbors began to gossip and press for explanations, the Shakers feared a second witch hunt. Faced with a public relations crisis, they decided to close their Meetings to visitors, which limited exposure to potential converts and healthy growth of Shaker population.

The Era of Manifestations came to a close as trance encounters began to taper off and ritualized group activities were halted. As the Spiritualist movement caught its stride, Shakers were already sweeping the shiniest fruits of revelation under the rug. The few Gift Drawings that were kept became the treasured possessions of Shaker children, only to be discovered a century later tucked into books or stashed away in drawers. However, many Shaker Gift Songs continued to be sung. The most famous, “Simple Gifts,” was played by Yo-Yo Ma at the inauguration of former President Obama. The perceived risk, subsequent concealment, and impact of Gift Drawings speaks to the power, and danger, of mystical visual art, if not the precious hours of devotional labor it took to make and revive Mother’s Work.

Neptune is preparing to depart Pisces in 2026, for the initiating fire sign of Aries, known for breaking down barriers and inspiring people to see what is possible. Over the last decade, there has been an explosion in the mystical services market, which is now valued at $3 billion globally; witches have come out of the broom closet en masse.

The last time Neptune transited Aries, Victoria Claflin Woodhull announced her candidacy for US President in 1870. It is significant that as this article was being written, Kamala Devi Harris, who was born during an Aries Full Moon, was running a promising campaign to become the first woman president of the United States. It is certainly in part due to the visionary possibilities created by activists and mystics in the nineteenth century, when only white male citizens were afforded protections or public recognition, that we find ourselves able to envision women of color in top-ranking positions of power. However, the unseating of Congresswoman Cori Bush, a human rights activist and true representative of her constituents, shows just how far we still have to go for progressive change to become part of the political institution.

From the proliferation of spirit-speak in mainstream publications about art and culture to the success of magic-centric shows like the record-breaking Hilma af Klint exhibition at the Guggenheim or the “Like Magic” show at MASS MoCA, topics deemed “occult” are moving into the spotlight. The New York Times recently featured an opinion piece by Jessica Grose, “Are We in the Middle of a Spiritual Awakening?” Increasing numbers of similar headlines show that spirit-speak has traveled far from taboo in the mainstream media, even as academia struggles to validate these phenomena.

Still, the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA, a town famous for both punishment and empowerment of women’s magic, chose to cloak an astute collection of Spiritualist information and ephemera under a public-facing facade of less relevant, male-centered stage magic for their exhibition “Conjuring the Spirit World: Art, Magic, and Mediums,” on view through February 2. The dominant focus on magic show posters in their advertising and exhibition entryway, though beautiful, feels like a disservice to an otherwise well-researched and sincere historic survey of a femme-dominant mystic movement.

This show-title-to-content dynamic appears flipped with another upcoming exhibition at the ICA / Boston. Leaning further into spirited frameworks as they revive a Shaker-focused exhibition from 1998 “The Quiet in the Land,” the ICA will open “Believers: Artists and the Shakers” on February 13. This version of the exhibition will feature a relatively blue-chip array of artists from ICA director Jill Medvedow’s original lineup, as it also expands to incorporate a new group of mostly younger artists. Some added work appears likely to fulfill more typical art world translations of Shaker legacy into chilly hard-edged minimalism, but we “suspend our disbelief” as we wait to see how intentionally the work will engage in fervent and vulnerable expressions of spirituality and BELIEF.

Cauleen Smith, Pilgrim (still), 2017. Digital video (color, sound; 07:41 minutes). Courtesy the artist and Morán Morán, Los Angeles and Mexico City. © Cauleen Smith

It is exciting to see formerly closeted spiritual and cosmic conversations taking the stage, yet one wonders what we can learn from the past about the sustainability of applied values if we don’t foster care for spiritual practitioners, the longevity of their labor, and their informed and invested advocates. If established institutions primarily take and profit, promote but obscure, censor, or decenter psychic practitioners and devotees of the divine, it can strip a movement of its caring stewards and fail to uplift what it leverages for itself. The same sentiment can be applied as we see sudden show alterations that forsake trans and Indigenous artists or strictly censor social justice activists voices.

In August, for the 250th anniversary of the Shakers’ arrival from England in 1774, the living Shakers held a symposium, God’s Work Will Stand: The Shakers’ Ongoing Testimony, at Sabbathday Lake in Maine. The rare Gift Drawings, which attendees of the Great Awakenings pilgrimage had the privilege of privately viewing in situ last summer, were on view from September through January in “Anything but Simple: Gift Drawings and the Shaker Aesthetic” at the American Folk Art Museum in New York. It’s encouraging to see all of the above exhibits incorporating the work of new and living contemporary artists—including Jose Alvarez (D.O.P.A.), Shannon Taggart, Gordon Hall, Pallavi Sen, Mariam Ghani, and Cauleen Smith—honoring necessary commitments to voices of the living as we reflect on the influential accomplishments of the dead.

The mystics who peer into the past and foretell the future deserve better than what previous generations have offered. Let us use this moment of radical change to create sustaining systems of support for the body/mind/spirit of all creative souls. As the Shakers and Spiritualists believed that death was not the end, nor even a place far from here, the influences of their legacies only seem to grow, even as their footprints diminish.

—1 Richard Tarnas, Cosmos and Psyche (Plume, 2007).

—2 Great Awakenings refers to a series of spiritual revival movements during which many new, mostly Christian denominations broke away from tradition to embrace a more personal and emotional connection with God. The Second and Third Great Awakenings lasted from 1790 to 1930 and were prominent in western and central New York, which became known as the “Burned-Over District.” This name described the passionate fires of conversion that had already blazed through the area, leaving no unaffected believers.

—3 Karen L. Heasley, “Sojourner Truth: Slave, Political Activist, and Spiritualist,” September 1, 2020, https://spiritualpath spiritualistchurch.org/sojourner-truth-slave-political-activist-spiritualist/. —4 Molly McGarry, Ghosts of Futures Past (University of California Press, 2008), 3.

—5 Ann Braude, Radical Spirits (Indiana University Press, 1989), 21.