Photography has been a pivotal tool in defining identities since its inception two centuries ago. Studio portraiture, ethnographic photography, government-issued identification, and family snapshots all define their subjects differently based on their context. “Visual Kinship” at Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum presents a spectrum of photographic works by twentieth-century and contemporary artists to survey the ways in which photography can define the notion of family and connection. The four curators, Alisa Swindell, Thy Phu, Kimberly Juanita Brown, and Iyko Day, focus on the medium’s ability to champion visibility in the face of marginalization and erasure.

Drawn from the Hood Museum’s collection and loaned works from Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, “Visual Kinship” features thirty-eight works that unfold across three gallery spaces, each dedicated to a theme—relationality to land, formations of family, and kinship of care. Opening with Relationality, the show argues that we define ourselves not just through familial ties but through our connection to place and land. Coyote Park’s Pacific Diaspora Kin (2022) sets the tone, showing the artist embracing members of their chosen family amid a rolling, grassy hillscape. Their nude bodies are harmoniously interwoven, conveying a sense of individual and collective identity shaped through their connection to each other and the landscape.

Rania Matar’s neighboring portrait, Alae (with the mirror), Beirut, Lebanon (2020), shows a contemplative young woman looking out over the Bay of Beirut. She gazes toward the remains of the storage building that exploded in 2020 from improperly stored ammonium nitrate, killing hundreds of people and destroying surrounding neighborhoods. The use of the mirror and Alae’s placement in the frame, observing the landscape that has in part defined her identity, heightens the weight of her rumination as she considers her future. In the wake of such destruction, does she stay in a home that has revealed itself to be unsafe? What will happen to her Lebanese identity if she leaves?

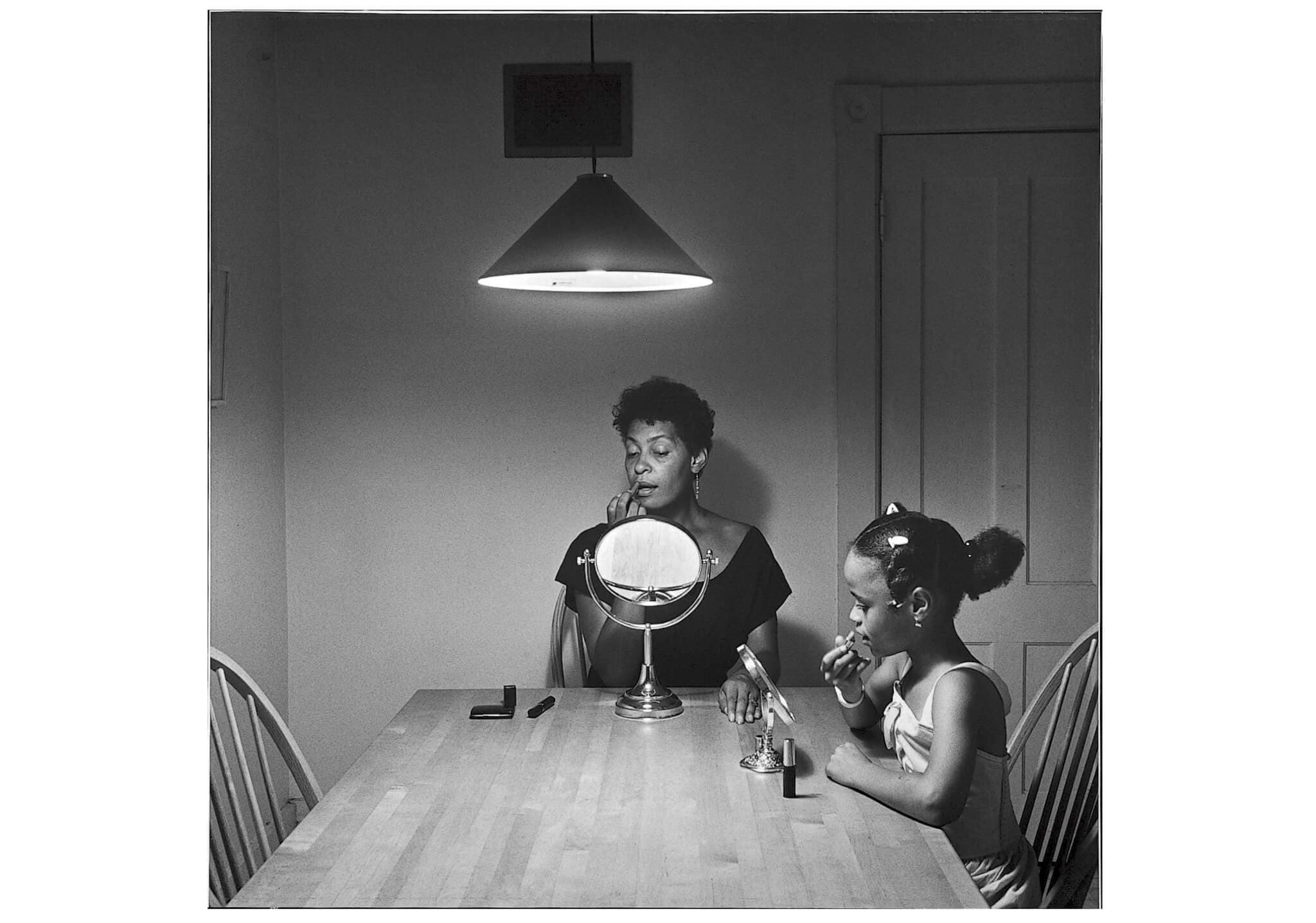

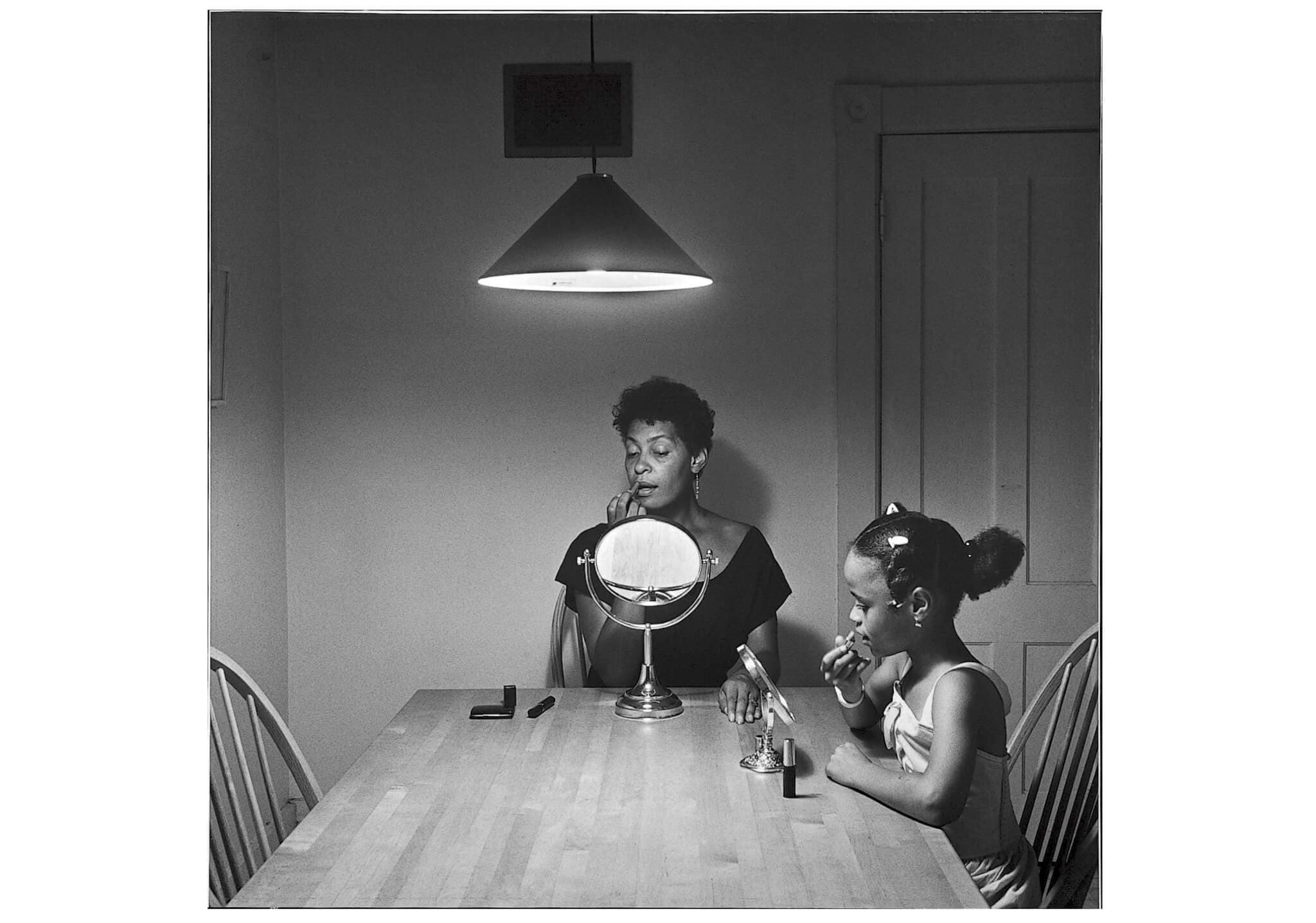

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Make-up with Daughter), 1990. Gelatin silver print. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth: Purchased through the Harry Shafer Fisher 1966 Memorial Fund; PH.991.46. © Carrie Mae Weems.

The Kinship and Care section is perhaps the most traditional application of kinship, leading with Carrie Mae Weems’s classic Untitled (Make-up with Daughter) (1990). Weems, seated at the end of a kitchen table opposite the camera, applies lipstick in front of a mirror as her daughter does the same. This carefully crafted portrayal of their bond elicits the habits and rituals of femininity that are passed down from one generation to the next.

Proximate works I Look Like My Momma (Self Portrait 1980) (2019), by Darryl DeAngelo Terrell, and Grandma Ruby, Mom and Me at Mom’s House (2005), by LaToya Ruby Frazier, are in poetic conversation, exploring the idea of inheritance from maternal forebears. Wearing makeup and their mother’s fur coat, Terrell looks unwaveringly at the viewer in their self-portrait. According to the wall text, the title came after the photo was taken, when Terrell’s mother remarked that they looked just like her, capturing the indescribable way in which our family lineage is reflected in ourselves. Frazier, who is known for documenting the post-industrial landscape of her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania, shows three generations of her family. Leaning against the chair her grandmother sits in and resting a hand on her mother’s shoulder, Frazier memorializes the place and the family that has shaped her.

Kali Spitzer’s Be & Madeline (2022), in which a mother and her adult nonbinary child embrace, builds on this notion. The photo, part of Spitzer’s An Exploration of Resilience and Resistance: Kin series, documents familial ties to counteract the ongoing erasure of Indigenous and mixed-heritage people. In this work, Be and Madeline fit together like two puzzle pieces, supporting each other and conveying the strength of their bond by facing the viewer directly. Like other works in this section, Spitzer uses physicality and presence to translate the emotional and spiritual bonds between family members into visual expression.

Nancy E. Rivera, Self-Portrait, American Daughter, 2017, 2020. Embroidery floss on cotton cross stitch fabric. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth: Purchased through the Contemporary Art Fund; 2024.42.5. © Nancy E. Rivera. Courtesy of Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth.

The middle gallery features a number of works that address how social and political issues intersect with personal identity, with a particular focus on the effects of cross-cultural migration. Two of the strongest examples use textiles to redefine the photograph, embodying the Formations of Family theme by tying the images to cultural traditions and family lineages.

Eun-Kyung Suh’s Nathan Twedt (2015) wades into the layered identities of transracial adoptees. Part of a larger series, Suh asked Korean-born adoptees to reflect on their experiences of being raised in white American families. Twedt’s portrait is transposed and fragmented into a series of sheer, square textiles inspired by Korean wrapping cloths called bojagi. Arranged as an incomplete square, the material forms what the artist calls a vessel, bridging Twedt’s Asian heritage with his white upbringing. In his contemplative expression, Suh captures the loss Twedt grapples with in this hybrid, liminal identity.

In a nearby case, five embroidered headshots from Nancy E. Rivera’s ongoing Family Portrait series tell the artist’s immigration story through her family’s collective experience. In a nod to her grandmother’s cross-stitching, Rivera renders government-issued identification photos into embroidery floss on cotton fabric. The works’ versos reveal the overlapping threads, speaking to the entanglement of her Mexican American identities. Using a craft passed down through generations, Rivera transforms a tool of state surveillance into milestones in her family’s journey from one home and culture to another.

Other works in this space lose the thread. Tseng Kwong Chi’s San Francisco, California (1979) is part of the artist’s East Meets West series, in which he donned a Zhongshan, or Mao, suit, and played the persona of “Ambiguous Ambassador,” posing next to iconic American landmarks. There are elements in this work that are echoed in other photographs on display—the series is, in part, a cultural critique of stereotypes and Asian identity in Western culture. It is difficult to find a familial narrative in this work, even if the definition of relationality has been stretched to include connections to land and culture. It is one of the moments in the show in which the focus seems to be more on identity formation writ large, rather than the ways in which family structures and influences identity.

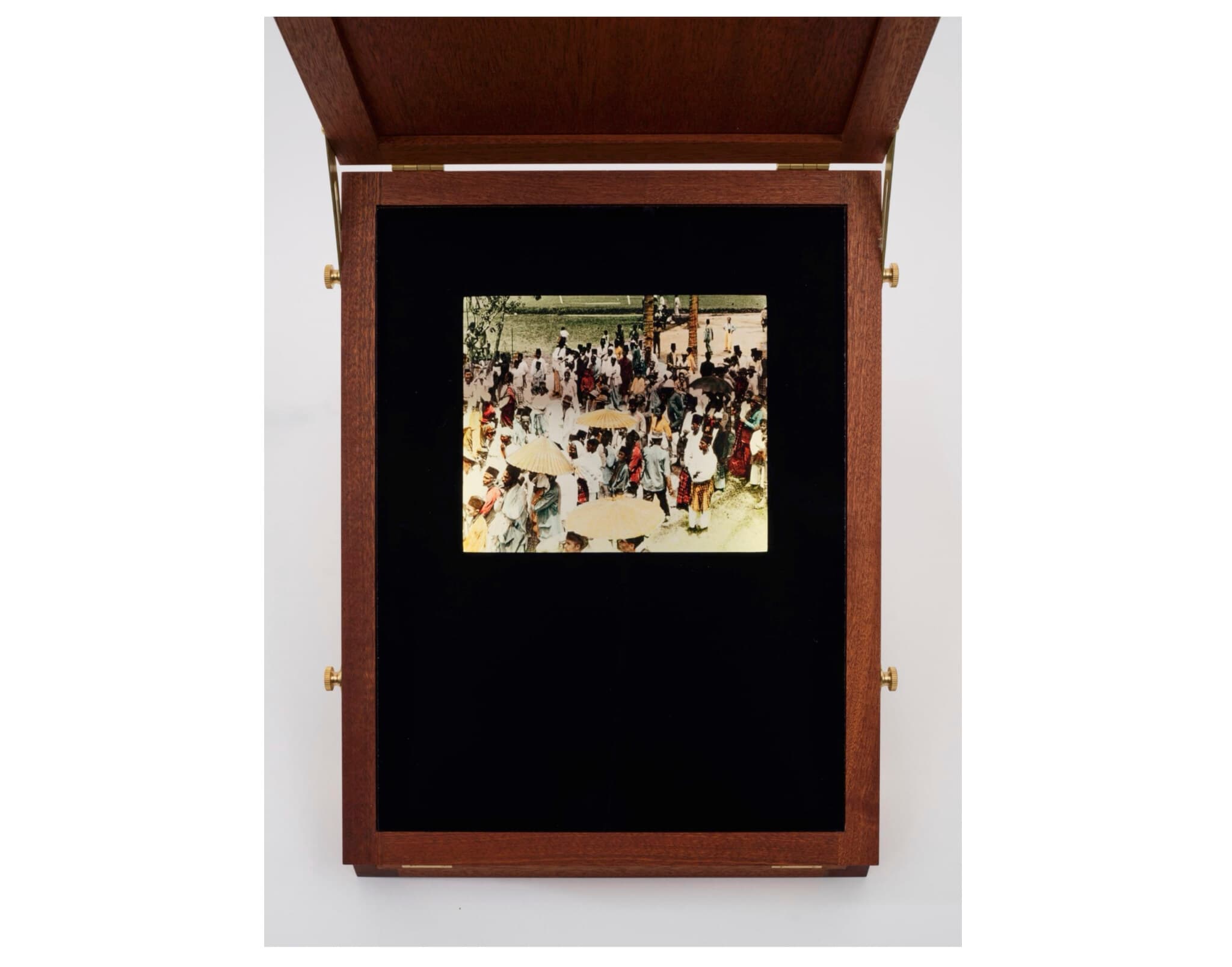

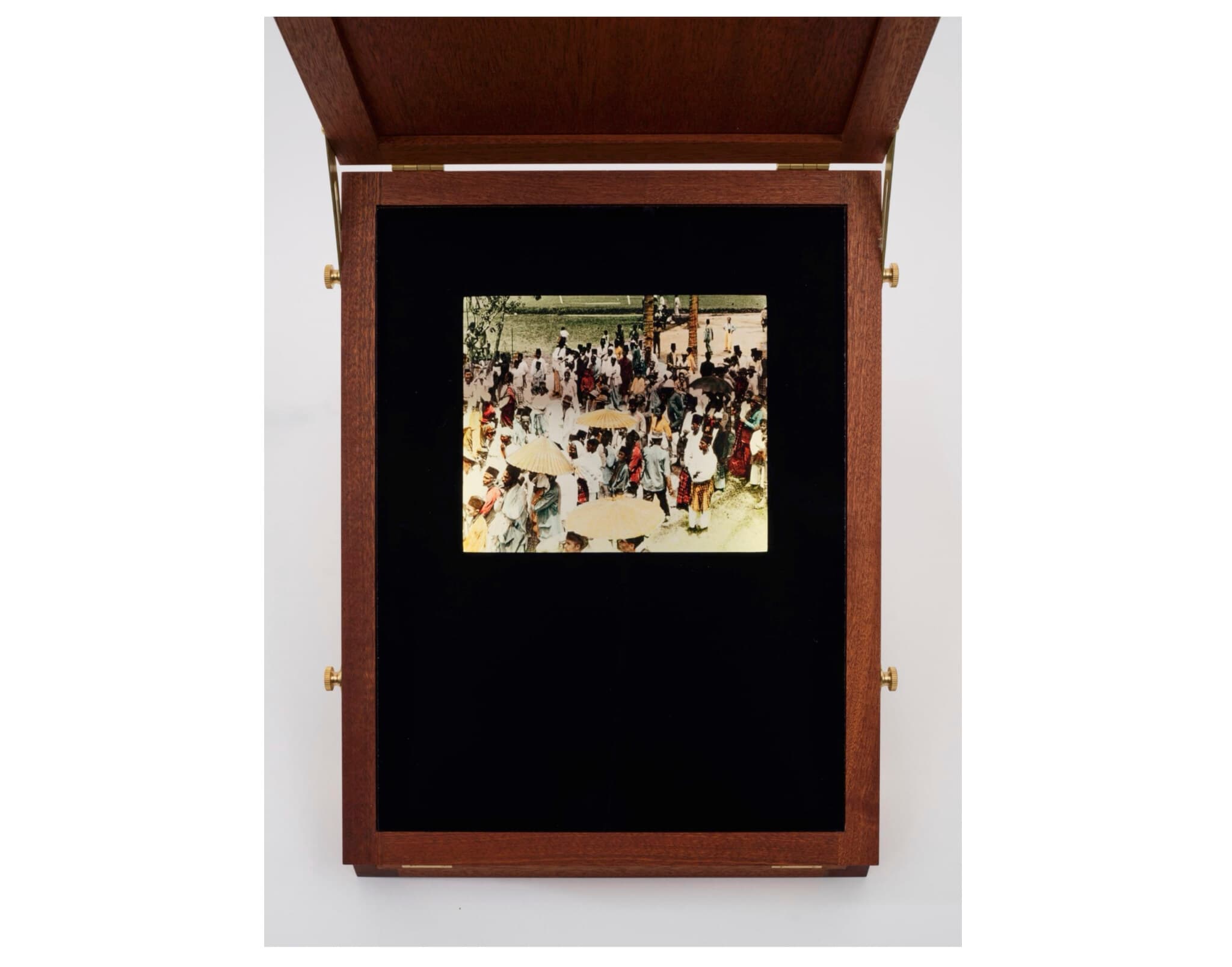

Sim Chi Yin, The Suitcase Is A Little Bit Rotten, Crowd, 2022. UV print on glass, light box, replica vintage stand. Glass plate: 30.5 x 23 cm (stand: 33.5 x 26.3 x 60 cm). Photo by South Ho. Courtesy of Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth.

The final gallery is dimly lit and dedicated to Sim Chi Yin’s site-specific installation The Suitcase Is A Little Bit Rotten, (2022–2023). Ten wooden workstations illuminate magic lantern slides Sim has doctored to include images of her son and her grandfather. Sim’s grandfather, a Malayan anti-colonial activist, was executed in 1949 and never met his grandson, but the two meet in the alternative universe the artist created. On the far wall, Sim’s film Time Travels With A Rotten Suitcase (2025) loops through a series of magic lantern slides that contrasts the tropical beauty of Southeast Asia with the brutality of British rule, particularly during the twelve-year anti-colonial war known as the Malayan Emergency. Sim spins a speculative version of her family story by repurposing a visual tool of colonialism. She doesn’t erase the horror and exploitation of the original images, but she offers a new, personal context in which to understand this history.

“Visual Kinship” is a timely exhibition, particularly in the context of a college campus in this historical moment. It offers an opportunity to find commonality and to consider the ways in which our individual identities are shaped by societal and cultural forces. In a “post-truth” era where we can create realistic images through prompt generation and must question everything we see online, it can feel as though photography is experiencing a tectonic shift. Yet “Visual Kinship” foregrounds two things. Its expansion of what constitutes lens-based reminds us that artists will continue to push the medium into new territory, and its focus on historically marginalized identities demonstrates the value of using photography as a tool to create a broader sense of self.

“Visual Kinship” is on view at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College through November 29, 2025.